On the corner of race road and privilege place

New exhibit at The Durham Museum examines race more closely

Along one wall of the exhibit hangs portraits of several multi-ethnic individuals. Their ethnicities are listed, and then, in their own handwriting, they wrote about how they define their race and themselves. “There wasn’t any defining features that are distinct through race,” Skoumal said. “Fingerprints can’t even be differentiated through race.”

November 15, 2019

White. Black. Brown. Our skin tones in the United States seem limited to just a few colors, but travel to Brazil and a person’s skin could be ebony, honey colored, dusky tan, cashew, cinnamon–the list goes on.

Opening September 28th, 2019 and lasting until January 5th, 2020, is The Durham Museum’s RACE: Are We So Different? exhibit. It is the brainchild of the American Anthropological Association, an organization of scholars and practitioners dedicated to the study of humans, past and present. Through their collaboration with the Science Museum of Minnesota and funding from groups like The Sherwood Foundation, a Nebraska social justice organization, the showcase came to life. It is the first national exhibition that explains race through the different lenses of biology, culture and history.

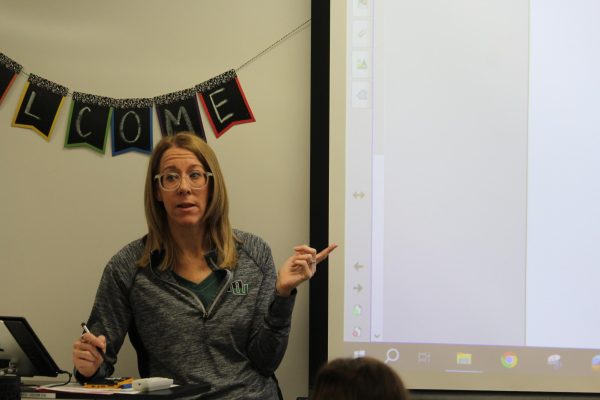

When Human Diversity teacher Dana Blakely found out about the exhibit, she knew it would be the perfect field trip to correspond with the class’s first unit on race.

“We don’t have a diverse school,” Blakely said. “It’s one of the disadvantages of our students, not only from a life perspective, but an education perspective. So I hope that looking at the displays emphasised the challenges different races face.”

The exhibit walks visitors through many different racial myth-breaking studies. The British scientist Francis Galton found no patterns that distinguish race in the fingerprints of English, Welsh, Jewish and African schoolchildren. The same goes for blood types and height–they aren’t related to any certain groups of people.

“When we looked at the displays asking ‘Who do you think has this type of fingerprint?’ or ‘Who is this tall?’ you couldn’t tell,” junior Lily Dame said. “There are a lot of stereotypes. Don’t judge anyone by what they look like because we are all human.”

Humanity is something we all share–it breaks skin color boundaries. But the phrase “We are all African” adorning a table at the exhibit probably isn’t something heard very often.

Africa has been inhabited a lot longer than other places, such as North America and Europe, allowing its population to develop small mutations and genetic changes over thousands of years. When people started to leave the continent, some of Africa’s genetic variation came with them.

And, according to the exhibit, the high intensity of the sun in Africa made for a darker skin color variation in human evolution. Where a person’s ancestors lived can point clues to their skin color because the frequency of our independently inherited traits is a result of past environmental conditions.

“World geography and human geography fit well with the exhibit,” Blakely said. “It was really interactive. There were a lot of activities you could do to drive home the academic point each display was making.”

One such display was made of a small screen and some buttons. As visitors listen to a voice, they can look at six faces on the screen and try to decipher which voice belongs to which person. Once visitors are fairly certain they know who is speaking, they can press the button to reveal the speaker.

72 percent of subjects, in one study, could accurately distinguish people’s ethnicity on the phone, even when the speaker just says “hello,” making linguistic profiling prevalent in the world today.

For some, sounding a certain way or even being stereotyped to sound like a certain group can determine whether they get a call back.

But race is just a human invention–a recent one at that.

“The exhibit was created to explain how race is a socially constructed concept,” Blakely said. “Race was created around the time when Christopher Columbus happened upon and classified people. Previously it was by wealth and religion and now it has progressed into more modern challenges.”

The sign in the exhibit with the bold labels “White” and “Colored” may not seem modern, but it was only around 60 years ago that those signs hung above water fountains and bathrooms. That is an example of when racism, not race, comes into play.

African Americans have been pegged for their hypertension, but it is not strictly because of the color of their skin. Studies have shown that their elevated blood pressure is due to the stress of racism in their everyday social environment.

After carefully going through the exhibit, visitors may find that fact a little less surprising.

At many spots in the exhibit there were invitations to relay personal experiences on a piece of paper to later become a part of the exhibit. One entry told the story of her first time reading the n-word. She got upset and cried, but her teacher told her she couldn’t feel that way because “racism doesn’t exist anymore.”

That belief is held by many people.

The exhibit makes a point of mentioning how Native Americans have been turned into mascots. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows painted them as primitive and savage, and now sports teams, like the Chiefs, Indians and Redskins, carry on that view for some.

In addition, discrimination in mortage lending creates huge wealth gaps. The average net worth of an African American family is about one-tenth of a white family’s average. And since African Americans, Native Americans and Hispanics are more likely to be turned down for mortgage loans, they lose not only housing opportunities but the chance to make more money down the road.

It is because of these modern day issues that exhibits like RACE: Are We So Different? are popping up.

“As America grows, interacting with other races is inevitable,” junior Blake Skoumal said. “It’s better to learn about it now.”

Make sure to check out the exhibit before it leaves on January 5th, and find out if we really are so different.