Sexism starts in the classroom

Gender disparity in school needs to be addressed

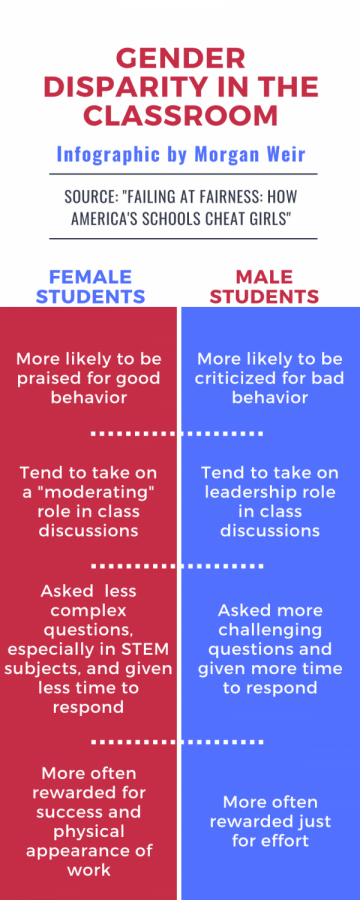

David and Myra Sadker, authors of “Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls,” found that there are major differences in the expectations, attention and praise given to students by teachers based on gender.

February 8, 2021

Article 26 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims that everyone has the right to an equal education regardless of factors like gender. On the surface, it seems like the U.S. has accomplished that. Girls are no longer denied entry to public schools and universities due to their gender. In fact, women outnumber men in higher education enrollment, and they have lower high school graduation rates. However, a deeper look at the state of education reveals that gender inequality is still rampant in schools.

If you were to ask any high school girl for an example of sexism in schools, many of them would probably point to dress codes, and rightfully so. Dress codes are written to target female students, and girls are punished for violating dress codes at far higher rates than boys. But there are also dozens more ways that gender bias shows up in the classroom, many of which are not acknowledged or talked about.

Researchers David and Myra Sadker observed public and private schools across the country for a few years and found major disparities in the way different genders were treated in the classroom. Their findings, detailed in their book “Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls,” paint a picture of an education system that serves as the taproot of gender gaps and inequalities in later life.

They found that teachers give different amounts and types of attention to different genders. Boys were called on more than girls and asked more challenging questions, particularly in STEM subjects. If they hesitated, teachers were more likely to give them more time or reframe the question. With girls, they were more likely to repeat it and ask someone else. Other studies have confirmed that boys get more attention from teachers throughout school. They are much more likely to get verbal and nonverbal attention from gym teachers specifically. This attention disparity reinforces, and is likely driven by, the idea that boys are “naturally” more aggressive while girls are more submissive; where boys demand attention (and are expected to demand more attention), girls are told to wait quietly for it.

Studies have also found that boys and girls are praised for different things. Girls’ work is more often praised for physical appearance, like neatness, rather than content. They are often rewarded for success where boys are praised just for effort. They are also criticized more for incorrect answers while boys are praised more for correct answers. When it comes to behavior, girls are more often praised for good behavior (even if it isn’t related to the task or lesson) while boys are criticized more for bad behavior. This all reinforces the bias that girls’ effort and knowledge is less important than appearance and success. This may explain the trend of girls having higher GPAs than boys; from a young age, they are taught to hold themselves to a different standard, and to associate their self worth with their grades since they are praised for success and results rather than effort or knowledge.

These differences in treatment impact what students think they are capable of. Boys are more likely to enroll in STEM classes and take higher level versions of those classes. As a result, there are significantly less women in STEM fields, which contributes to the bias that boys are better at math and science despite brain scans proving this to be false. While boys are often pushed into higher paying career roles (engineers, doctors and lawyers), girls are more often pushed into lower paying career roles that emphasize the stereotypically feminine role of caretaking (like nurses or teachers). It may be that women dominate these lower paying careers because they are seen as better suited for low paying jobs, or that these jobs are seen as women’s work and therefore undervalued in terms of pay. Regardless, the point stands; the subtle differences in how teachers treat students has a major impact. The wage gap still stands at around 82 cents to every dollar a man makes.

The effort to end gender disparity in the classroom will have to be an effort between students, teachers and society at large. It isn’t an issue of overtly sexist teachers but of unprocessed biases and assumptions. Still, the issue needs to be addressed. If we want to create a country with equal pay, equal career opportunity, women in STEM, men in caretaking roles and less gender discrimination in general, it needs to start in the classroom. For teachers, that means being able to acknowledge bias in order to alter teaching habits. Intentionally giving all students more time to answer questions, being aware of what praise is given to whom or asking how stereotypes are being enforced in the classroom are all places to start. For teens, it means looking back on how the gender bias you experienced growing up shaped your perception of yourself and others. It also means being an ally for other peers in the classroom.

Gender bias and inequality currently thrives in classrooms, and it has a major impact on how students view themselves and their worth. However, it doesn’t have to be this way. Schools provide the perfect opportunity to educate future generations and break the cycle of stereotypes and sexism. It will only take a group of dedicated students and educators who are willing to acknowledge their unconscious bias and do something about it.

Alya • Mar 16, 2023 at 11:25 am

This issue needs to be brought up more and makes me so mad reading this. Excellent job.