Nebraska needs to join the ERA of equality

After almost a century, it’s time to finally ratify the Equal Rights Amendment

photo courtesy of History Nebraska

People protest the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in the Lincoln Capitol Building in 1973. Nebraska became the first state to ratify the ERA in 1972 but became the first state to withdraw in 1973.

February 28, 2020

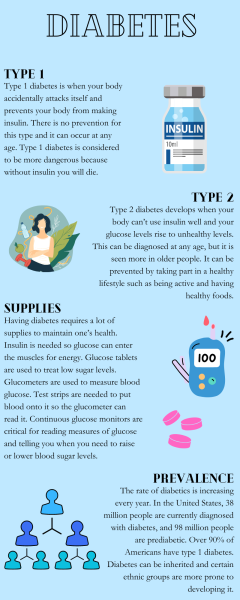

On March 22, 1972, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment to fight sex-based discrimination and ensure equal rights which was introduced in 1923. The active clause of the ERA would read: “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Nebraska became one of the first states to ratify it in 1972. By 1973, 30 states had ratified and brought the ERA well on its way to the 38 states necessary to make the amendment official. Public opinion polls from the time were leaning heavily in favor.

Then the Stop-ERA campaign came along. Led by Phyllis Schlafly, the campaign catered classic demonstration tactics from the second wave feminist movement to fit their arguments and turn the tide on ERA advocates. They hung signs that read “don’t draft me” on baby girls and baked apple pies for the Illinois Legislature. The amendment, they claimed, would devastate the “traditional family structure” and make women’s lives harder. The campaign worked.

By 1982, the deadline imposed by Congress to pass the ERA, it was just three states short of the necessary ratifications. The ERA was all but dead until 2017, when Nevada ratified the amendment and brought it back into the spotlight. Illinois followed in 2018 and on February 12th, 2020, Virginia became the 38th and final state needed. All that was left was for Congress to eliminate the 1982 deadline. With the House of Representatives voting 232-183 in favor of removing the deadline on February 13th, all that’s left in theory is for the Senate to follow suit. However, it may not be that easy.

The Republican-majority Senate is unlikely to get rid of the deadline and even if they did, the Supreme Court likely wouldn’t find in court that it was ratified fairly. Even Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who has spent much of her career speaking out against sex-based discrimination and fought for a gender clause on the 14th Amendment, says that if the ERA is going to be added to the Consitution, the ratification process needs to restart, and many politicians and legal scholars agree.

The reasoning for why the process should restart is complex. Some of it has to do with the fact that the deadline has already passed, but a lot of contention has also sprung up around five states, including Nebraska, who rescinded their ratification. While the Constitution doesn’t allude to a state’s right to rescind ratifications, many (including Justice Ginsburg) have noted that if the states who recently joined are counted, then it wouldn’t necessarily be fair to also count the states who withdrew. The issue is made even more complex by the fact that two states tried to withdraw their ratification for the 14th Amendment but the action was declared “irregular, invalid, and therefore ineffectual” at the time, and the two states were counted towards the 38 necessary ratifications. Some have used this precedent to argue that the state attempts to withdraw are legally null.

Besides the issues of state withdraws and deadlines, there have been other arguments against the amendment. One of the most common (and least creative) is that “women’s equality of rights under the law is already recognized in our Constitution,” as Arizona representative Debbie Lesko claimed during a Senate debate about the ERA. Eighty percent of Americans believe the same thing, according to a poll by the ERA Coalition/Women’s Equality Fund.

This might be a valid argument if it held any truth, but the fact is that the only specific protection women are guaranteed in the Constitution is the right to vote. While there is legislation protecting against employment discrimination (in the Civil Rights Act) and discrimination in federally funded schools (in Title IX), the ERA could expand protections to women in prisons, schools, workplaces and sports.

The fact that women aren’t equal is perfectly illustrated in the statistics regarding gender-based violence. According to the CDC, one in four women will experience domestic violence and one in three will experience sexual violence. Data from a 2018 survey by Stop Street Harassment suggests that 81% of women have experienced sexual harassment.

In the words of Alice Paul, who drafted the ERA and was one of the first to advocate for it in 1923, “we shall not be safe until the principle of equal rights is written into the framework of our government.”

In regards to legislatures, the ERA would force states to enforce anti-discrimination acts and gender violence prevention laws. It would require them to intervene in cases of motherhood or pregnancy discrimination, which the Supreme Court ruled were not included in Title VII. The currently existing laws to protect gender equality are constantly under threat and subject to expiring, being amended, taken back or not being renewed.

There’s nothing to stop the next administration or Congress from rolling back existing protections. The fact that gender equality is not exclusively guaranteed in the “supreme law of the land” means that women’s rights are always being threatened, and this is not some hypothetical dystopian scenario–it’s happening constantly. Last year, Secretary of Education Betsy Devos proposed new rules stemming from Title IX, which bans gender-based discrimination in federally funded schools. The rules would allow cross-examination of survivors and narrow the definition of sexual assault on college campuses, making it easier for perpetrators to get away with and more emotionally taxing on survivors. The Violence Against Women Act, which protects survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault, also faced issues last year as the Senate stalled its reauthorization after relentless lobbying from the NRA, which shows just how fragile and at-risk these laws are without the ERA.

In regards to courts, it would create clear judicial standards for cases that involve sex-based discrimination and provide a sturdy legal defense in court cases to protect women’s rights. Strict scrutiny would be required in legal cases revolving around gender-based discrimination, which means the government would need to prove a law/policy serves compelling, rather than just substantial, government interest and that essentially there was no less discriminatory way to do the same thing.

Fifty-five men (not a single woman) served as delegates writing the Constitution, 44 men (also not a single woman) have been president, and only one woman was serving in Nebraska’s unicameral during the vote to rescind the state’s ratification of the ERA. Men have run politics for centuries, and men have served their own political interest for centuries. It’s time that we enter an era where gender equality is part of the framework of the country and where women have a say. Fundamentally, the question of whether the Equal Rights Amendment is worth it is a question of whether this country truly believes the Constitution should guarantee equal rights for everyone.