College: why so pricey?

Students in America find themselves choosing an education based more on affordability than what it has offer them

May 9, 2019

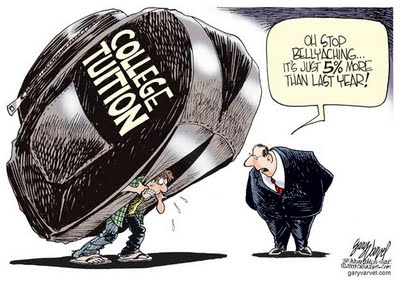

Before the automobile, before the Statue of Liberty, before the majority of today’s colleges existed, the rising cost of higher education shocked Americans: “Gentlemen have to pay for their sons in one year more than they spent themselves in the whole four years of their course,” The New York Times said in 1875. Over-indulgence was to blame, the writer argued: fancy student apartments, expensive meals, and “the mania for athletic sports.” And this was over a century ago.

Today, the U.S. spends more on college than almost any other country, according to the 2018 Education at a Glance report. All told, including the contributions of individual families and the government, Americans spend about $30,000 per student a year, nearly twice as much as the average developed country.

“The U.S. is in a class of its own,” says Andreas Schleicher, the director for education and skills at the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), and he doesn’t mean this as a compliment.

Schleicher said, “Spending per student is exorbitant, and it has virtually no relationship to the value that students could possibly get in exchange.”

Only one country spends more per student, and that country is Luxembourg, where tuition is nevertheless free for students, thanks to government outlays. In fact, a third of developed countries offer college free of charge to their citizens, and another third keep tuition very cheap at less than $2,400 a year. The farther away one gets from the United States, the more baffling it looks.

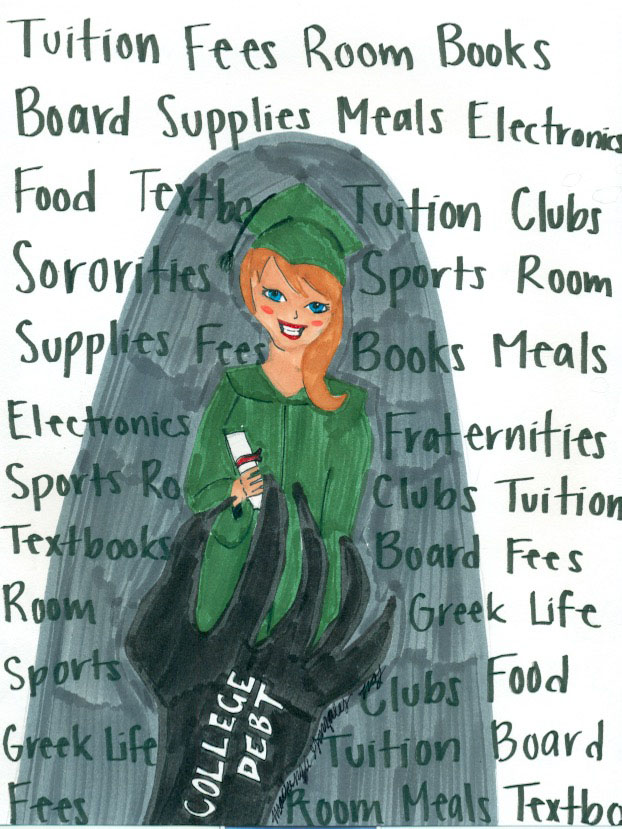

At a glance, it seems obvious to blame the curdled indulgences of campus life: fancy dormitories, climbing walls, dining halls with open-fire-pit grills, and most of all, college sports. Certainly sports deserved blame. New international data provide some support for this narrative. The U.S. ranks No. 1 in the world for spending on student-welfare services such as housing, meals, health care and transportation, a category of spending that the OECD lumps together under “ancillary services.” All in all, American taxpayers and families spend about $3,370 on these services per student, more than three times the average for the developed world.

One reason for this difference is that American college students are far more likely to live away from home. And living away from home is expensive, with or without a climbing wall. Experts say that campuses in Canada and Europe tend to have fewer dormitories and dining halls than campuses in the U.S.

“The bundle of services that an American university provides and what a French university provides are very different,” says David Feldman, an economist at William & Mary College. “Reasonable people can argue about whether American universities should have these kind of services, but the fact that we do does not mark American universities as inherently inefficient. It marks them as different.”

On closer inspection, the data suggest a bigger problem than fancy room and board. Even if colleges were to zero out all these ancillary services tomorrow, the U.S. would still spend more per college student than any other country except, again, Luxembourg. It turns out that the vast majority of American college spending goes to routine educational operations, like paying staff and faculty, not to dining halls. These costs add up to about $23,000 per student a year, which is more than twice what Finland, Sweden, or Germany spends on core services.

“Lazy rivers are decadent and unnecessary, but they are not in and of themselves the main culprit,” says Kevin Carey, the author of The End of College.

In their book, Why Does College Cost So Much?, Feldman and his colleague Robert Archibald argue that the business of providing an education is so expensive because college is different from other things that people buy. College is a service, not a product, which means it doesn’t get cheaper along with changes in manufacturing technology, economists call this “cost disease.” College is a service delivered mostly by workers with college degrees whose salaries have risen more dramatically than those of low-skilled service workers over the past several decades, creating an endless feedback loop of pricey colleges producing pricey employees.

College is not the only service to have gotten wildly more expensive in recent decades, Feldman and Archibald point out. Since 1950, the real prices of the services of doctors, dentists and lawyers have risen at similar rates as the price of higher education, according to Feldman and Archibald’s book. “The villain, as much as there is one, is economic growth itself,” they write.

The absurd cost of higher education in the US creates conversations between high school students and their parents that end up focusing more on the cost of said education rather than the quality. With the seemingly perpetual rise of college pricing affecting how students choose their college, and subsequently their career, America must ask themselves if the motives and priorities of their colleges are in the right place.