The classist politics of food insecurity

Food deserts make healthy eating a privilege

photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture

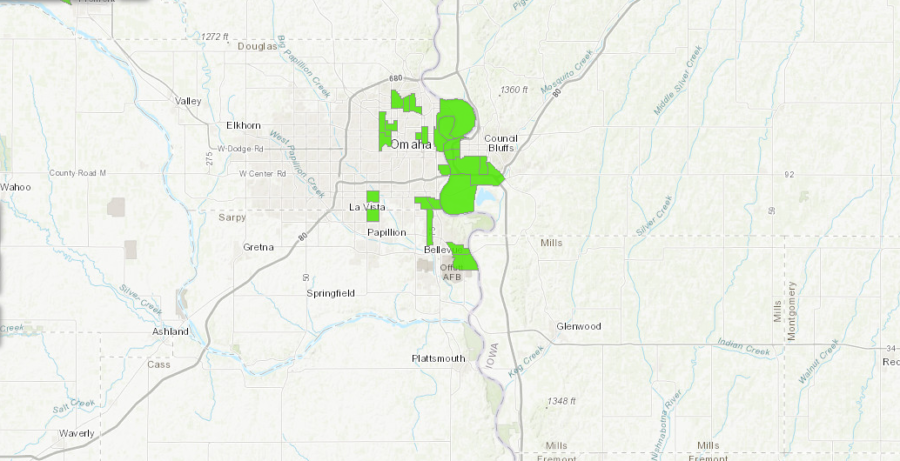

A food desert tracking map by the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows food deserts in the Omaha area. In accord with the national trend, many of them overlap areas with high concentrations of poverty.

April 26, 2021

Rising rates of cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes, dental disease and other nutrition-related diseases have become a focus of criticism against the U.S. in the past decade. At first glance, it seems like America is just lazy, unhealthy and unmotivated to improve their fitness and nutrition. Often, the proposed solution is to educate people on the importance of eating more vegetables or exercising for 30 minutes a day. These solutions, however, don’t touch on the real underlying cause behind America’s nutrition problem: poverty.

Today’s high schoolers likely remember former First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign, which set ambitious goals for eradicating childhood obesity and left its footprint on children’s television channels, nutrition facts labels and the school cafeteria. Through its Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which provided financial incentives for “healthy food retailers” that opened in low-income areas, Let’s Move! became one of the first federal campaigns to try to confront food deserts in the U.S. Despite that progress, the government, and the country in general, has failed to do anything on a larger scale about poverty as the root cause of America’s eating problem.

This is an issue that impacts people in all corners of the U.S., including our community. In the Omaha-Council Bluffs area, around 16% of the population deals with food insecurity, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.” That amounts to approximately 133,000 in the community who can’t afford to put food on the table according to the Omaha Community Foundation’s data analysis project, Landscape Omaha. Those living below the poverty line are four times more likely to lack access to healthy food.

Omaha’s high concentration of food deserts is a significant contributing factor to its struggle with food insecurity. The USDA maps food deserts based on the accessibility of stores that sell healthy foods and availability of transportation for the local population. Simply put, food deserts are areas where people live far from grocery stores and tend not to have reliable access to transportation to get to stores. This makes it more difficult, time-consuming and expensive to purchase food, and it often means that people turn to alternative sources to eat, like fast-food restaurants.

Because of food deserts, healthy eating is often unaffordable for those living in low-income households. Everyday privileges that many of us take for granted, such as carefully choosing which brands we want to buy or planning balanced meals, are not realistic.

How can you take the time to find and cook homemade meals every day if you’re working constantly just to get food on the table? How can you spend 40 minutes at the grocery store if you’re a single working mom and have young kids who need to come with you? How can you go to the store every week to buy fresh groceries when you’re trying to take the time to read to your kids at night and help them with their homework on top of working? How can you think about how your diet will impact your health long-term when you’re focused on how you’re going to feed your family that week?

The conversation around nutrition in America often operates under the assumption that everybody has the privilege to think about the lasting effects of their diet. For some, longevity is the goal when it comes to forming healthy habits that sustain your body and keep your organs healthy for the rest of your life. For at least 133,000 people in the Omaha area, however, that isn’t an option. The priority, by necessity, is survival.

None of this is by chance; low-income people are targeted. Even for those who want to make healthier choices, unhealthy habits and foods are, figuratively, shoved down their throats. A recent study from the University of Connecticut suggests that fast food advertising is primarily aimed at children of lower socioeconomic status. Low-income areas have higher rates of fast-food restaurants per capita than more affluent areas. Conversely, in a phenomenon known as supermarket redlining, health food stores such as Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s are far more prevalent in higher-income parts of town across the U.S.

This has profound implications for low-income people. Beyond the myriad of associated health issues, nutrition deficits mean that kids go to school hungry and families struggle under the stress of food insecurity. It impacts the grades children get, the relationships they have with their parents and the body image they build. When these children become parents themselves, they tend to pass on the habits they have created, turning food insecurity into a generational cycle. Escaping that cycle requires more than determination; it requires strong community support to break the patterns of hunger, self-image issues, poor diet habits and poverty that are passed down.

Those coming from a place of privilege need to refrain from making assumptions about unhealthy eating in this country and recognize the root of the problem. America’s issue with nutrition has nothing to do with a lack of self-control or bad decision-making; it is a direct result of poverty.