The school-to-prison pipeline

The dangers of policing in school

Information provided by the U.S Department of Education Office of Civil Rights

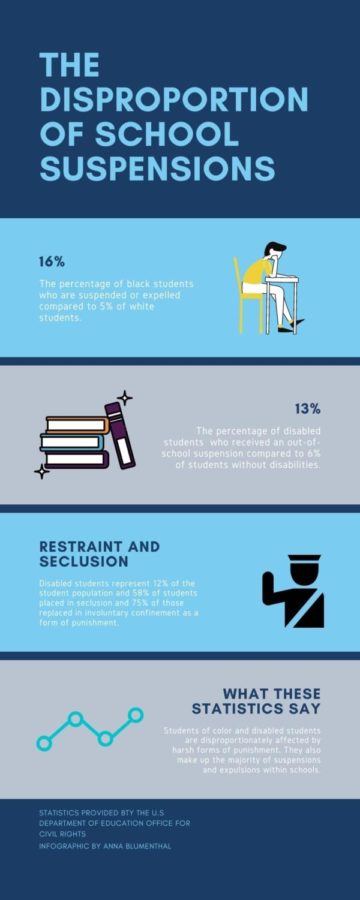

School suspensions have become a common form of school discipline, but these suspensions affect students disproportionately.

March 10, 2021

A rise in the concern of students’ safety after the emergence of school shootings, such as the shooting at Columbine High School, led to schools bringing in police enforcement to protect students. These policemen, known as Student Resource Officers (SROs), were originally called to prepare for a rare occurrence. However, as SROs started to get involved in everyday issues, more and more kids have become subject to harsh forms of school discipline.

According to statistics reported by the US Department of Education, about 92,000 students were arrested during the 2011-2012 school year. When an SRO arrests a student, they are turned over to the juvenile court system for punishment, rather than discipline, through the school. This makes it easier for students to obtain a juvenile record for small issues, such as talking back to teachers or getting into fights with peers.

Harsher punishments have also led to this change in school discipline. High suspension rates have led to what the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research refers to as “school connectedness,” which is associated with academic achievement as well as with healthy behaviors. With new “zero-tolerance” policies emerging within school buildings, an increase in school suspensions has led to students feeling a lack of safety within their schools. These policies immediately subject students to punishments for what could be minor infractions.

While any student can get caught up in the school-to-prison pipeline trap, students of color and disabled students are disproportionately affected by these policies. The injustice begins in preschool, with a study done by the U.S Department of Education Office for Civil Rights finding that while only making up 18% of the preschool enrollment, black children represented 48% of children receiving more than one out-of-school suspension. The trend continues in high school in which black students are three times more likely than white students to face suspension or expulsion. Students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to experience an out-of-school suspension and represent 58% of students placed in seclusion or involuntary confinement.

Even if school administrators do not turn directly towards police in schools or the juvenile justice system as a form of discipline for students, these policies make it more likely that a student will end up in contact with the juvenile probation system. In a study conducted by Texas A&M University, it was found that of students disciplined in middle school or high school, 23% of them ended up in contact with a juvenile probation officer compared to the 2% of those not disciplined.

The intent of SRO programs in schools is to enhance schools’ safety and sometimes that can work. Their presence may help deter aggressive behaviors such as fighting between students, threats and bullying. However, studies of actual SRO safety outcomes show mixed results and while in some schools they help deter outbursts of violence, that is not a universal outcome.

While parents may believe that harsh punishments are a reflection of the student body and that police officers in schools foster a safe learning environment, the SROs are worsening the internal culture of schools. Minor discretionary offenses, such as classroom disruption and insubordination, could land a student in prison. Getting police out of schools and implementing more counseling, rather than punishment for insubordinate behavior, would both foster a safe learning environment and help with school connectedness. Helping students succeed rather than leading them towards a life in a cell should be the main end goal. Students need to be treated like kids and not like criminals.