TikTok’s fatphobia problem

Weight loss content can be harmful

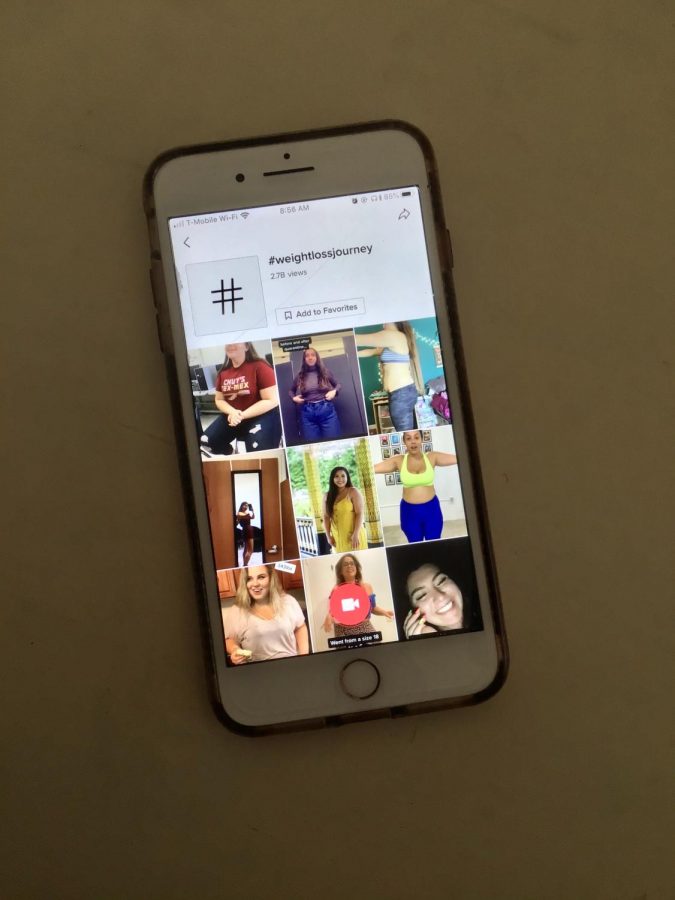

The tag “weight loss journey” on TikTok has almost 3 billion views. The “weight loss” tag has over 13 billion views, and “what I eat in a day” has 4 billion views. Some tags, such as “pro-anorexia,” which promotes eating disorders, have been blocked on the app.

November 20, 2020

With over 850 million active users, TikTok has quickly become one of the top social media apps on the market. Its content ranges from dance trends to comedic skits to glow-up videos. It has become a platform for political activism, social connection and artistic expression. But, like any other social media app, it has a dark side.

Some of the most inadvertently harmful content can be found at the intersection of health and glow-up videos on the app. These videos, which exploded in popularity during quarantine, include “what I eat in a day” vlogs, workout plans and weight loss journeys. They seek to motivate people to improve their physical health, usually with the underlying goal of achieving an external “glow-up.” While these videos may have good intentions, they get a lot wrong.

They may be motivating to some people, but they do nothing to challenge the deeply misguided stigmas about weight in modern society. This is especially true of weight loss journey videos, which reveal some of the worn-out myths about physical health. The underlying theme behind many of these videos is that weight loss is a matter of pure will, that the simple formula of “workout more and eat better” will lead to a healthier life and a lower weight. This is a common narrative which has been disproven by a growing body of research. Numerous studies have shown that “on again, off again” dieting can actually lead to weight gain in the long term and is linked to heart disease, inflammation and high blood pressure. Other studies have proven that the tired trope of “calories in calories out” just isn’t true. Some have found that motivation isn’t the main influence in weight loss because genetics, health conditions, socio-economic status and dozens of other factors play a role. Videos on TikTok that are less than 60 seconds could not possibly capture these incredibly complicated nuances.

One of the biggest health myths furthered by weight loss videos on TikTok is that health and size are directly correlated. We live in a world where we think we can tell how healthy someone is just by looking at them. One of the inevitable results of this assumption is that we praise people for weight loss without context. In a short TikTok video, there’s almost never context. Weight loss can be a result of so many things: eating disorders, mental health issues, physical illness or poverty. Because of these complexities, we have to ask ourselves what we are really celebrating when we comment on these videos. Are we celebrating health, or are we celebrating thinness? Despite popular belief, these two terms are not interchangeable.

Weight loss videos leave out these critical complexities in an attempt to present a digestible narrative. Their popularity is based on the idea of “the journey,” where someone starts out at a higher weight and, presumably through dieting and sheer will, manages to lose weight and find their “happy ending.” The nuance of body image is reduced to a simple script that starts with scenes of someone staring, disheartened, at their body in the mirror and ends with them, skinnier and smiling, at their new self. The struggles, shifts and, most notably, relapses that come with losing weight are left out to fit TikTok’s 60 second cap. For the creators of these videos, TikTok is a way to tell their story, and they are free to tell that story however they want, but viewers need to keep in mind that they’re not witnessing a “journey.” They are witnessing a highlight reel.

A keystone of the script for weight loss journey videos is the “before and after” mentality. Viewers devour the 60 second progression of losing weight, often shown through progress pictures taken by the TikTok creator in a mirror. They revel in the contrast between the first few pictures and the last few pictures without considering the connotations behind the video. The first few seconds of the weight loss videos, the “before,” suggest that joy comes with weight loss, that your life is on hold until you look a certain way. The before is what the creator is glad they dont look like anymore. It’s something to frown at, something to be repulsed. The last few seconds, the “after,” are a reminder to viewers of what they may be missing: confidence, happiness and success—the implied results of thinness. The after is what we should all strive for, what we should all celebrate unconditionally. For most of the creators, the before and after is something they take pride in, as they should. But they should also consider the implications of these videos and what it says about people who look like their “before.”

The other critical piece of the script of weight loss TikToks is the “happy ending.” The magical thinking of thinness, prevalent in pop culture, suggests that weight loss is a cure-all, not just for physical health, but for mental health, social status and overall well-being. It suggests that with thinness comes stronger friendships, more popularity, a better love life and even career success. This is a narrative that has been well-worn in movies and TV for decades, and on TikTok, where the format is short videos with happy endings, it’s just as popular. It’s also just as inaccurate. Confidence will not come from weight loss. It comes from overcoming the constant external messaging about what you “should” look like, and that messaging does not stop once the number on the scale drops.

One of the most tragic consequences of this magical thinking and diet culture on social media in general is eating disorders. Studies have shown a strong correlation between social media use and risk for developing an eating disorder. TikTok, with its rise in “pro-eating disorder” content during 2020, is clearly part of the problem. Teens should not be using workout routine videos and “what I eat in a day” vlogs on TikTok to make personal, medical decisions, but that doesn’t stop TikTok’s algorithm from recommending these videos to teens. Eating disorders have been increasing among females between the ages of 15 to 24 in the past few decades. They are the second most fatal mental disorders with one eating disorder related death every 52 minutes. The problem of diet culture and fatphobia on TikTok is, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

The conversations and stories shared on social media play a critical role in either stopping or furthering that message. There’s nothing wrong with being proud of reaching a goal, but TikTok users need to think about the underlying societal implications behind their content, especially on a platform whose audience is largely young, impressionable viewers. TikTok’s glow-up side needs to realize that the real glow-up is building people up no matter what they look like, and escaping society’s narrow views of beauty, health, worthiness and confidence.

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, help is available. Contact the National Eating Disorders helpline