Voting is a right, not a privilege

Suppression efforts escalate during 2020 election

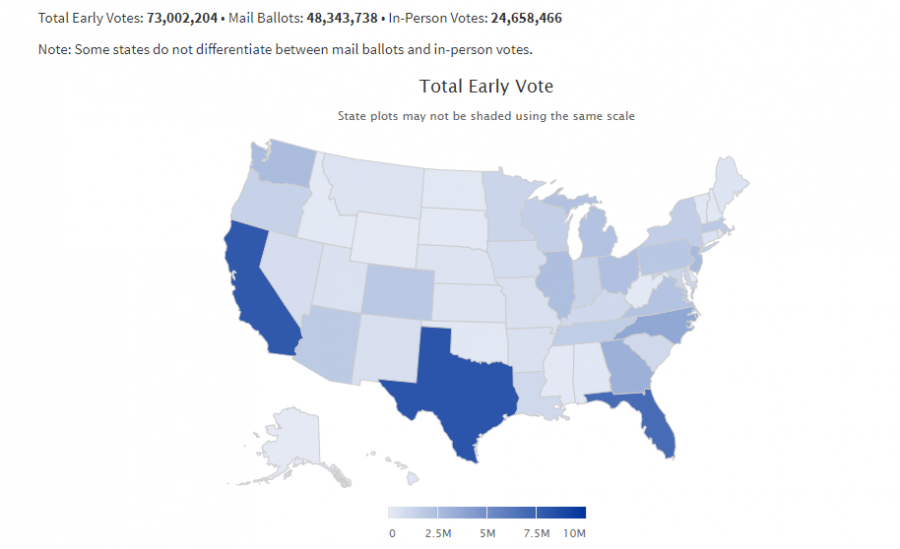

Photo courtesy of US Elections Project

Over 40 million people have voted by mail this year already, according to data from the US Elections Project. That includes almost 400,000 mail-in ballots returned in Nebraska. The 2020 election has brought unique challenges for voters, and unique opportunities for politicians looking to suppress voting.

October 29, 2020

After the passage of the 15th Amendment, which prohibits states from disenfranchising people based on race, voter suppression tactics became commonplace in the US. Poll taxes, grandfather clauses and literacy tests all targeted African Americans and prevented them from voting. A Louisiana literacy test from the late 1950s, for example, allots ten minutes for 30 questions and warns that one wrong answer means a failed test. One of its questions asks test-takers to “print a word that looks the same whether it is printed frontwards or backwards.” Thanks to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, these literacy tests are a thing of the past. Voter suppression, however, persists.

During the 2020 election, held in the middle of a pandemic as case numbers hit new records in the US, voters are facing unique barriers. Many voters are relying on mail-in voting to cast their ballots while limiting their exposure; already, over 70,000,000 people have voted early, with almost 50,000,000 of those votes coming from mail-in ballots. The United States Postal Service, suffering from a lack of funding, warned that they may not be able to keep up with this surge of mail-in ballots, so voters have been encouraged to deliver their ballots to special drop-off boxes. Politicians in some states have used this to limit the accessibility of mail-in voting. In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott ordered officials to limit ballot drop-off sites to only one per county. In Houston’s Harris County, the third largest county in the country, the County Clerk, Chris Hollins, had planned twelve drop-off sites. Limiting that to one would “result in widespread confusion and voter suppression,” according to Hollins.

In a highly contentious debate, politicians are doing whatever they can to boost their party’s power, including using tactics designed to restrict certain people’s ability to vote. Many of these tactics were prevented by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, until key provisions of that act were overturned by the Supreme Court in 2013. Within hours of that ruling, states started working to implement voter suppression policies. GOP officials in North Carolina, for instance, made plans to end same day voter registration, restrict early voting and require ID’s, all of which, they knew, would lower voter turnout and disproportionately impact minorities. This year, they went to court to make it easier to reject ballots with minor mistakes. Almost 7,000 votes have been contested so far in North Carolina. The risk of ballot rejection is three times higher for Black voters than white voters this year in the state. Similarly, in Florida, Hispanic voters have a rejection risk 2.6 times higher white voters. An investigation from USA Today Network, Columbia Journalism Investigations and Frontline predicts: “more than 1 million people will likely lose their ballot on Nov. 3. That’s the best case.”

Like the ballot rejection rates, many voter suppression tactics impact voters of color disproportionately. Voter ID laws, which are in effect in 35 states this election, “substantially alter the makeup of who votes and ultimately do skew democracy in favor of whites and those on the political right,” according to a 2017 study published in the Journal of Politics. Black people and other people of color are less likely to have the required government-issued ID. These ID requirements lead to a lower voter turnout of two to three percentage points, according to the US Government Accountability Office.

Exact-match systems, which require signatures and names on a ballot or registration form to perfectly match government records, are also discriminatory. According to American Bar Association, 80% of over 51,000 people impacted by Georgia’s exact match system in 2018 were Black. That year, African-American candidate Stacey Abrams lost the election by 55,000 votes. The exact match rule also impacted some Hispanic voters who have a hyphen in their name that does not appear on their drivers license. In a country where so many groups of people fought for so long to guarantee their right to vote, it’s insulting and unethical that politicians are designing tactics to suppress these groups.

High school and college students in particular should be concerned because many voter suppression tactics target young people. Residency requirements and photo ID laws, for example, can be difficult for students attending college out of state. There are also restrictions on mail-in voting for young people in some states. In Texas, an effort to waive these restrictions during the pandemic was turned down in court. Restrictions to same-day voter registration also hurt youth voter turnout since new voters aren’t always aware of registration deadlines.

In order to combat these tactics, there has been a surge of messages encouraging people to learn about their state’s voting rules and regulations and have a plan in case something goes wrong at the polls. There has also been a surge in legal challenges to voting restrictions; according to Stanford’s Healthy Election Tracker, there have been more election-related lawsuits in the last year alone than in the last two decades. While many of these cases have resulted in victories enabling less restrictive and suppressive voting rules, there have also been many losses. The Supreme Court upheld a decision in Pennsylvania to count ballots that arrive up to three days after Election Day, and they blocked an attempt to undo the waiver on mail-in ballot witness requirements in Rhode Island. However, in eight out of eleven emergency election-related appeals filed since April, they upheld blocks to restriction lifts that would have made it easier to vote.

The argument for heavier restrictions, especially with mail-in voting, is often that it will prevent voter fraud. The current president has been very outspoken about this, once claiming that widespread mail-in voting would lead to “thousands and thousands of people sitting in somebody’s living room, signing ballots all over the place.” A number of studies in various states have found that voter fraud is incredibly uncommon. A 2017 study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that the overall fraud rate in the US is between 0.00004% and 0.0009%, and a Washington Post analysis found one proven instance of voter fraud during the 2016 election. In Oregon, where postal elections have been held since 2000, only 14 cases of fraud have been reported. Politicians’ baseless claims of voter fraud are nothing more than thinly veiled attempts at suppressing voters and lowering voter turnout for groups who oppose them.

Especially in the middle of a pandemic, politicians should be protecting the right to vote and making it more accessible, not suppressing and limiting it for political gain. Threats to voting, particularly mail-in voting, have left people burdened with the choice of either exercising their most basic democratic right or protecting their health. These threats have raised a lot of critical questions leading up to Election Day, many of which have been brought up in court. One of the most important questions is whether this election will be a fair one. If politicians continue to turn voting into a privilege only appointed to a few and denied to marginalized people, the answer to that question will be a resounding “no.”