Black and white

Omaha has a long history of racial segregation

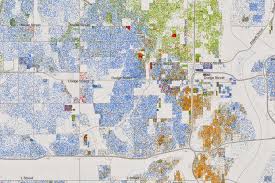

photo courtesy of University of Virginia

A map of Omaha created by Dustin Cable at the University of Virginia using 2010 census information. It is the most comprehensive map of racial distribution in America that exists, as reported by Wired, since it maps individuals. Each dot represents a person: blue shows white people, green shows African-American, orange shows Latino and red shows Asian.

January 24, 2020

When looking at a map of racial demographics in Omaha, a clear pattern emerges. The city can be effectively divided into north, south and west on racial lines; the black community largely resides in the north, Hispanic in the south and white in the west.

Looking at racial segregation on a local scale is incredibly important as it reveals the larger global pattern. It also is necessary for global citizens to understand not just the patterns that exist in their communities, but the reasoning behind these patterns. Without having a deeper level understanding of the historical and modern systems that influence the world, there is no basis for critical discussions about privilege and equality.

Omaha’s segregation issue largely began during World War 1, when African Americans moved North during what is known as the Great Migration. Those who migrated to Omaha mainly went to South O where there was an abundance of packaging jobs. Later, they migrated to North O for housing opportunities and the chance to work in or start a business.

Residential segregation was driven by a collection of policies and social systems that were most evident in Omaha before and during the ‘60s, such as restrictive covenants and redlining. Arguably the biggest factor in the enforcement of this segregation was Omaha’s public school system. Omaha Public Schools (OPS) maintained black schools in North Omaha throughout the early to mid 1900s. This was furthered by teacher hiring practices, zoning laws, the residential segregation that existed, and the school administrators and community members who pushed this system. Racial segregation therefore drove residential segregation and vice versa. From this, it’s clear that the modern de-facto racial segregation is intrinsically connected with economic segregation.

In 1973, the US government filed a lawsuit against OPS stating that the school district was intentionally carrying out actions to racially segregate its schools in violation of the 14th Amendment and Civil Rights Act. The United States was able to effectively win the case; the result was that OPS had to institute a court-ordered busing program to racially integrate its public schools.

The busing program was successful on paper. Schools had become more integrated and students of color were attending what used to be predominantly white schools. However, when Omaha passed a bond to end the program in 1999, most Omaha schools resegregated in large part and went back to similar racial makeup as they had in the ‘60s. Not only was all the work undone but a deeper truth was revealed; Omaha would have to work much, much harder to integrate and create equality within its education system–but it didn’t seem the white lawmakers and citizens were eager to do that.

The busing program also drove, in part, a trend throughout the late 1900s of white flight to West Omaha. Families who didn’t want their kids to go to the more integrated schools in OPS fled to the suburbs where they could be sent to schools in suburban or independent districts with white majorities. During the four years after busing began, white student enrollment in OPS tanked by over 15000.

In 2005, as a response to this continued white flight of families and students to West Omaha, OPS announced they would annex some white majority schools in Omaha limits that were being controlled by the independent or suburban districts. The purpose of this was to create a more equitable tax base and foster integration through magnet programs. However, some white suburban parents rebelled against this and the Nebraska unicameral came up with a measure to prevent the absorption of these schools by OPS. It was made to look like an issue of money by those who opposed it; they said that it would hurt their kids since OPS didn’t get the same property taxes that West O did. In reality, it had more to do with race. West Omaha had around 9% minority rate at that point, whereas OPS had around 56%.

The unicameral’s measure to stop the absorption instead offered a plan for a “Learning Community” made up of 11 school districts which would run under a common tax levy and would be required to work together to encourage voluntary integration. The levy would later be canceled in 2017 despite some concern that this would hurt the poorer schools like those in OPS.

In April of 2006, Nebraska state senator Ernie Chambers, the only African American in Nebraska’s unicameral at the time, proposed an amendment to this measure. His plan would have divided Omaha schools into three by racial majority with a white, Hispanic and African American district. It was approved with a vote of 31-16 and signed into law by the governor

The idea behind the plan was that black parents, students and teachers in OPS would have control over the black majority schools. Chambers argued that segregation already existed and this would not enforce that more than it already was enforced but would allow black Omahans living in North Omaha the opportunity to ensure their children were treated fairly in the educational setting. Critics (and there were many) argued that this was nothing more than state-sponsored segregation and it did nothing to help with integration or equality within OPS. Inevitably, the amendment faced legal challenges and was struck down.

The implications of this historic and continued segregation go far beyond the obvious injustice of denying children in OPS access to quality education; it is the start of a vicious cycle that explains the persistent and ruthless inequality that exists in Omaha to this day.

When African-American kids in Omaha are forced into low-quality schools and denied any chance of integration where they may be given equal (or ideally equitable) opportunity as the generally wealthier West Omaha kids with access to resources, technology, classes, extracurriculars and more, they end up falling into the cycle of low test performances and low scores on ACT and college tests. In a society where test scores play such a prominent role in determining what colleges you can get into and whether you can get a scholarship, these kids then inevitably end up being denied that same chance at being admitted into colleges which may have led to higher paying jobs.

As previously discussed, a lower income means less of a realistic possibility that anyone would be able to afford the higher costs of West Omaha houses. This means that should these kids become parents themselves, their kids are denied the chance to go to the more resourced and financially well off schools in West Omaha which are financed by the higher property taxes of the expensive houses in West O. The cycle, viciously and persistently, continues, illustrating the intersection between racial and economic inequality as it exists in Omaha.

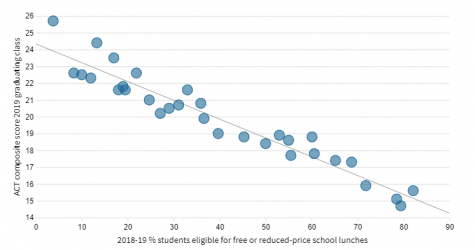

This cycle of injustice is not just hypothetical or speculated. Its truth is revealed by educational and economic data. Out of the US’ 100 largest metro areas, Omaha has the third highest black poverty rate and the highest for black children. The high school graduation rate for black students in Omaha in 2017 was around 79% compared to 93% for white students. In 2019, 42% of white Nebraskan students who took the ACT met three or four of the ACT college-readiness standards compared to only 9% of black students and 14% of Hispanic students who took it. On the same note, there was a close correlation between poverty levels and ACT scores as shown by this chart from the Omaha World Herald. With an 8.3% poverty rate, Millard West averaged 22.6 on the ACT in 2019. Comparatively, Omaha South, Omaha Benson and Omaha Bryan all have poverty rates above 78% and the average scores were all below 16.

In a democracy like America’s, it is important to recognize that policy doesn’t impact culture and deeply rooted societal beliefs as much as culture and society impact policy. Therefore, if Omaha has any hope of changing this modern trend of segregation and inequality they will have to do more than put a few programs into place and sign some laws. They will have to intentionally work to acknowledge the anti-black, anti-immigrant history and the social systems they have put in place to further cycles of inequality. If white Omahans aren’t willing to face and combat these internalized ideals and beliefs, nothing will change.