Recycling can’t save the earth

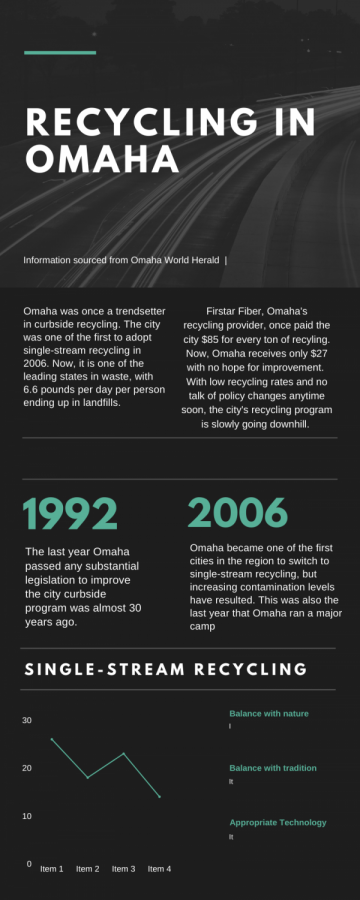

Recycling in Omaha is on a downward trend. See info-graphics for stats

November 19, 2019

From reducing waste to saving energy, it’s hard to ignore the benefits of recycling, but people don’t generally talk about its flaws. Only 34 percent of recyclable materials are actually recycled according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Even if that number was higher, there are still major issues posed by America’s out-dated recycling program which put the validity of recycling in question.

A recently popular type of recycling known as single-stream has further exacerbated the problems. According to the Government Advisory Associates, there was an 82.6 percent increase in waste facilities using it in the last ten years, including Omaha’s facilities. With single-stream, recyclables don’t need to be separated before being collected. Instead, everything is put into one bin before being picked up and taken to a recycling center to be sorted. While this system has proven much more convenient for people, it also leads to high levels of contamination when non-recyclable or dirty items are thrown in with the rest of the recyclables. Often, this means that the entire batch has to be disposed of rather than recycled. According to the National Waste & Recycling Association, about 25 percent of what ends up in recycling bins is contaminated.

Contamination proves that recycling can sometimes do more harm than good and has led to a major problem with China, who was importing more than half of the world’s paper and plastic waste by 2016 according to The Economist. The US started shipping a lot of its waste to China around 1992. It was easier to ship it overseas than to invest in better recycling methods and technology, and it made sense considering that the US did not have much of a market for recyclables unlike China with its booming manufacturing industry. With a quarter of America’s recyclables being contaminated after the adoption of single-stream methods, however, China has become fed up and announced last year that it would implement major changes to its import of waste. They are now refusing to take in recyclables with above 0.5 percent contamination rate. Generally, what the US sends is 30 to 50 times that number.

These changes have sent the US into a frenzy over what to do with the tons of recycling piled up they are unable to ship to China. One-third of Americans’ recyclables were exported to other countries prior to 2018 as reported by the New York Times. With no place to send them to, some US cities are stopping recycling programs or dumping whatever can’t be sold into landfills, including major cities like Philadelphia and Portland. Thousands of tons of recycled materials in US cities are just getting dumped into landfills because of China’s new rule according to the New York Times, which proves how inefficient and fragile the recycling system is.

More importantly, China’s import changes have revealed existing flaws within America’s waste management system. Prior to the new rules, it was easy to avoid updating recycling centers and systems because China was the one dealing with the waste in the end. Cities across the country are now being forced to confront extremely outdated recycling systems; Omaha is no exception.

The last time Omaha passed any type of big recycling policy change was over 20 years ago. There are no clear plans for change anytime soon despite the fact that Nebraska’s recycling rate fell far below the national average, according to the Nebraska Recycling Association, with only about a little over half of eligible households participating. Omaha World Herald found that Nebraska takes fifth place in the country when it comes to sending trash to landfills. This problem goes far beyond the city’s poor recycling system as it directly connects with Omaha’s segregation issues. The Omaha World Herald reported that more affluent parts of the city like Millard have higher rates of recycling compared to areas like North Omaha. Even if Omaha’s government makes changes to the green bin program, it won’t be effective unless it directly addresses privilege in the community. Another major thing that needs to be addressed is plastic waste.

People buy one million plastic bottles every minute as reported by Forbes in 2018. Recycling may seem like an easy way to diminish the sense of urgency over this number, but the truth is that just because you put your recycling in the bin every week doesn’t mean it’s being recycled. Everyday items are increasingly being made from low-grade resin and other non-recyclable types of plastic. Even the stronger and higher grade types can only be recycled a few times before the quality becomes too low to reuse. National Geographic reported in 2018 that of the 6.3 billion tons of plastic waste produced since the mass production of plastic started in 1950, only nine percent was actually recycled.

It’s not just plastic that faces these dilemmas. Recycled paper has to be 99 percent clean to be sold for reuse by companies but it’s expensive to get it to that point when it’s mixed in with contaminated items in single-stream programs. Similarly, glass recycling is one of the most potentially useful because glass can be recycled an infinite number of times, but many cities including Omaha won’t pick it up curbside because it makes recycling unusable if it breaks.

Many of us like to think of recycling as a charity that we graciously donate to every time we drop something in a green bin, but the truth is that recycling is a business where the primary objective is profit. Much of recycling is run by major waste companies who have more interest in filling landfills because it’s cheaper than recycling. Waste Management, one of the top waste agencies in the country, has admitted that the economic viability of recycling is at risk because the cost to process recyclables has gone up but the price companies will pay for them has decreased. In short, waste has become less valuable. Recycled paper, for example, is not in as much demand because people are shifting more towards digital news and online text. Prices for recyclables are now at a fraction of what China once paid and are below what it costs to gather and ship which means that no one is making a profit. The fragility of the market for waste is further evidence that recycling can not be depended on to fix the earth.

As a result, many big waste management companies have stopped paying cities for their recyclables and instead are forcing cities to pay them high sums for recycling programs. In Stamford, Connecticut, for example, the city went from earning $95,000 from its recyclables to paying $700,000 in a year. The few companies that contribute 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, as reported by the International Panel on Climate Change, love that recycling pushes the responsibility of dealing with waste on to governments and tax-payers. Focusing on the harms of production and manufacturing shifts that responsibility on to the companies and forces them to deal with their own exploitative practices which is what needs to happen for us to have any hope of curbing climate change.

As messed up as the current recycling methods may be, it is impossible to deny the potential it has as an integral part of larger economic and cultural shifts. Moving towards a circular economy where products are made only out of reusable materials, used for as long as possible and then regenerated includes recycling as a key part of the process. However, it will only be productive if we also reject toxic consumerism as a culture and prioritize reducing over recycling. In 2018, according to Wasteline Omaha, people in Omaha recycled 16,975 tons. They trashed 139,471 tons. Clearly, if we are throwing away eight times the amount we are recycling, the problem isn’t just how we collect waste but the horrifying amount of waste we are creating.

Framing climate change, mass extinction, pollution and the destruction of our seas as the fault of individuals is dangerous when the solution clearly requires so much more than just turning off the lights when we leave the room or recycling. It’s a good starting point for making urgent and necessary systemic change, but it is also a dangerous stopping point. The WorldWatch Institute reported that in less than 15 years, worldwide waste is expected to double. As our consumerist problems grow, we won’t be able to hide behind recycling forever.