Seaspiracy conspiracy

Netflix fishing industry documentary stirs up backlash while shining light on marine destruction

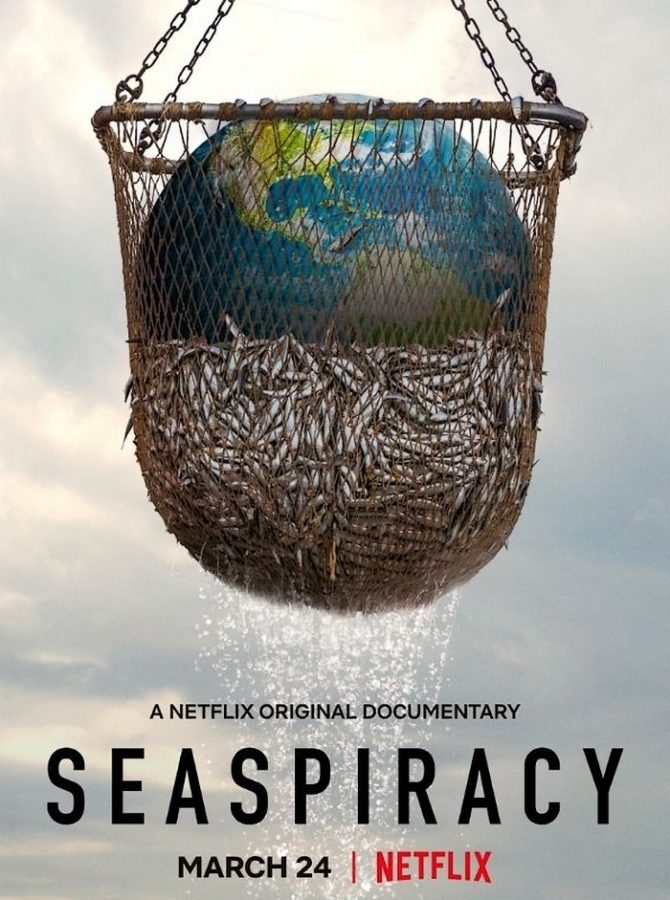

Seaspiracy details the corruption and environmental destruction of the commercial fishing industry. 3/5

May 19, 2021

Images of bloody whales washed ashore flash on screen. A voiceover narrates footage of trawling nets tearing up the ocean floor. An interviewee, with their face hidden and voice distorted, describes the horrors of enduring forced labor on fishing ships. These scenes, from Netflix’s hit documentary “Seaspiracy,” illustrate the violent destruction of our ocean by the commercial fishing industry.

The film, directed by Ali Tabrizi, made it to Netflix’s top 10 category in 32 countries. Tabrizi says it started as a look into beached whales and turned into an investigation of ocean destruction, human rights abuses and financial corruption. It educates viewers on the complexity of marine ecosystems while making an emotional appeal about the impact of overfishing.

Going into it, I anticipated the typical narrative about plastic straws, pollution and animal extinction. The documentary did not fit those expectations at all, which was not a bad thing; it touches on issues that I had never heard about before. It investigates whale hunting, the sealife entertainment industry, ghost nets, Dolphin Safe labels, mercury in seafood, grind-whaling, the shark fin industry, fish farming, the mafia-esque murders of boat observers and much more.

To capture the footage and investigate the issue, Tabrizi and his wife traveled to countries including Japan, the Faroe Islands, China and Thailand. Throughout the documentary, Tabrizi emphasizes the danger he is putting himself in, implying at one point that he could be killed for exposing this information. This, combined with the footage of the team being reported to police while filming and turned away from capturing video at seaports, makes for a dramatic hour and a half.

The film’s use of statistics is captivating, informative and moving. Near the middle of the documentary, a number flashes on screen warning that our oceans will be “virtually empty” by 2048. During a look into coral reefs, Tabrizi explains that 90% of big fish in coral reefs have disappeared. Another data point claims that while 250,000 sea turtles are killed by commercial fishing boats each year, only 1000 die from plastic straws in the ocean. The research that is woven throughout the movie adds to its authority and urgency, but are the numbers true?

The accuracy of the film’s research has been a topic of debate since its release. Following in the footsteps of its team’s first documentary, “Cowspiracy,” “Seaspiracy” stirred up controversy over some of its claims and research. Fishing companies, marine biologists and even a few environmental groups have contended that some of the information is misleading or untrue. The 2048 number, for example, is based on outdated research from 2006. Still other sources, like BBC, claim that the majority of the numbers are accurate and that the positive social impacts of the film negate any misleading information.

Like the research and statistics, the film’s organization is a mixed bag. The combination of hidden camera footage, animated graphics, interviews and first-person accounts work well for the variety of content covered — an animated visual could help viewers better understand the concept of trekking in one scene while footage of dolphins being caught and killed in trekking nets could add to the emotional depth in the next scene. This makes it engaging and interesting to watch, even for those who are not typically interested in science or marine life. However, it felt discombobulated and the storyline was not fully developed, which is one of the most important aspects in creating an impactful documentary. Rather than divide the information into larger segments with smooth transitions, the documentary jumps from one topic to the next.

The film makes up for this disorganization by covering some of the most important yet overlooked issues in environmentalism. Often, documentaries about sustainability neglect to acknowledge the human cost of environmental destruction. “Seaspiracy” dedicates a large portion of its run time to do just that; it explores the nuances of imperialism, poverty and cultural differences in environmental practices. It looks at how wealthier countries heavily subsidize the fishing industry to the point that their national stocks of fish are depleted. Their fishing boats move to the shores of poorer regions, like West Africa, where they continue to overfish and provoke hunger and economic issues for the local population. It also investigates slavery and abusive working conditions on fishing boats, namely in Thailand, where one interviewee describes being splashed with boiling water and witnessing their shipmates being thrown overboard by their boss.

The only issue I had with this part of the documentary was that, even after detailing the dependence on fish in many small, impoverished communities, it pushes cutting out seafood completely as the only viable solution. This sends the message that exploited countries should suffer because wealthier countries overfished and ruined it for everyone, which is a common theme in environmentalism; while rich countries cause the problem, impoverished countries pay the price. The documentary could have avoided playing into this by putting the blame solely on the wealthy commercial ships who overfish rather than on the local, subsistence fishers who have been using sustainable practices for decades.

Despite some of the misleading information and the holes in the overall argument, “Seaspiracy” was worth a watch because, if nothing else, I left with a lot of new knowledge on the ocean as an ecosystem, new terms to add to my vocabulary and, most importantly, a much deeper appreciation for the ocean and what it does for us.