Holding everyone accountable

Police brutality is a product of a flawed and failing institution

Police brutality has been a popular topic over the past year. With more and more stories coming out about the violence minority groups face from the police, people have taken a stand against the system. Minority groups are effected at a disproportional rate which has been more widely publicized following the murder of George Floyd.

April 23, 2021

On April 20, former Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, following the death of George Floyd. Many saw this as a step forward following conversations about the current failings of the policing system and the ways in which it needs to be reformed. The sad truth, however, is that this shouldn’t have been a monumental case that created a storm of divisive conversation surrounding who was “right” or “wrong.” In any other situation, the killing of an unarmed person would more than likely end in a criminal indictment, but the fact that the person doing the killing had a badge was used as a justified excuse.

This is one of many recent events that have shown a spotlight on the brutality police officers are able to enact while receiving little to no punishment for their actions.

This sort of behavior is a gross abuse of the title and power law enforcement is given, and the excuse that the officers didn’t know better or were confused about aspects of the situation aren’t strong points in the defense of such a heinous crime. It’s understandable that under certain circumstances there can be confusion, but within the George Floyd case, the public is able to see on video footage that there was excessive use of force.

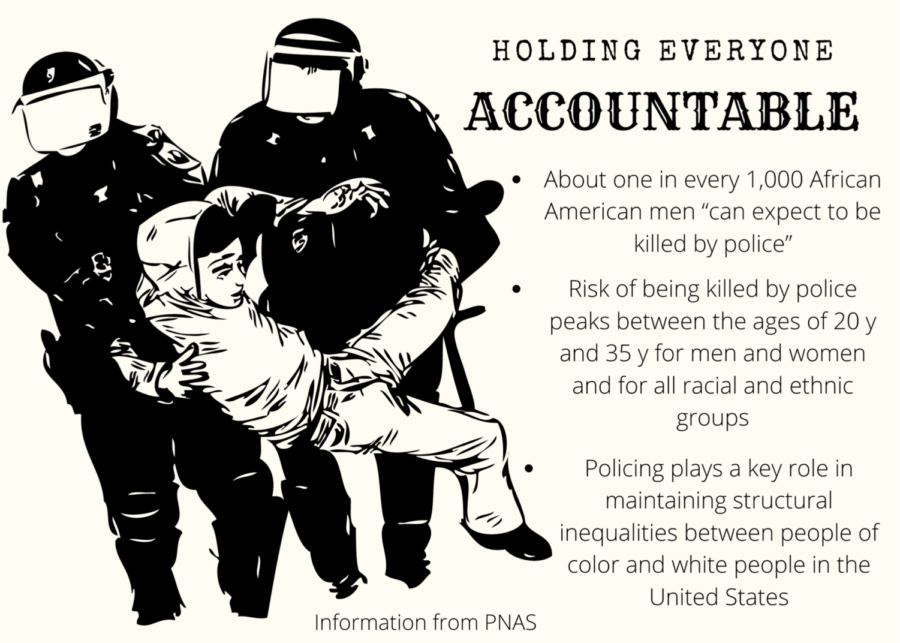

In recent months, we have seen a continuous stream of violence against minority groups, but specifically African American men. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) reports that over their lifespan, about one in every 1,000 African American men “can expect to be killed by police.” The statement that a minority group “can expect to be killed by police” is incredibly disturbing. The idea that a federally funded organization, which is intended to protect American citizens, will eventually be responsible for the death of anyone creates distrust amongst marginalized groups and the general public as well.

The PNAS goes on to state that, for young men of color, police use of force is amongst the leading causes of death. A common justification many take towards that statement is that people of color, specifically men, are more likely to participate in illegal activity. But it’s crucial to acknowledge the historical disadvantages that have plagued minority communities in the U.S. for centuries. An area where this inequality is blatant is in the wealth gap which is a contributing factor to actions some minorities take. According to the Center for American Progress, “African American families have a fraction of the wealth of white families, leaving them more economically insecure and with far fewer opportunities for economic mobility.” You can’t blame people for simply trying to survive in an environment that was forced onto them by Anglo-Saxon beliefs and practices that still occupy parts of our society whether we know it or not. Just because some minority groups face higher crime rates and incarcerations due to an already flawed justice system, it doesn’t make murder an appropriate punishment if they are suspected of breaking a law. Killing someone based on assumptions and connotations about their character is not a defensible excuse.

Although it’s important to better understand the difficulties minorities face within our community which can lead to these situations with the police, it’s equally important to understand how this extreme behavior is accepted and defended by law enforcement. Britannica explains that the unique institutional culture of urban police departments is a large factor in how officers are shaped, “with stresses on group solidarity, loyalty, and a ‘show of force’ approach to any perceived challenge to an officer’s authority. For rookie officers, acceptance, success and promotion within the department depend upon adopting the attitudes, values and practices of the group, which historically have been infused with anti-Black racism.”

The history of policing provides an interesting insight into the origins of these mentalities and practices. On NPR’s podcast “6-Minute Listen,” guest speaker Chenjerai Kumanyika, an assistant professor at Rutgers University, explains that “police really evolved around a lot — what I would call labor control. And so in the South, that was controlling slaves. But in the North, that actually had to do with controlling any inconvenient population, especially labor. And so the institution of policing is very much connected to the enactment of violence against strikers and union-breaking.”

With a system founded on the principles of harming and oppressing underprivileged groups, it’s easy to see the root of the issue. Just because their message changed from oppression to protection, it doesn’t mean the methods and mindsets have progressed in the same manner. With a past made up of a violent origin and nature, it’s understandable that those ideas have prevailed over the years.

That, however, doesn’t make it excusable. In recent months, we’ve seen a massive surge in a push for reform, rightfully so. There are many ways in which reform can dismantle the racist and violent system that has existed for far too long. New bill’s like the H.R.7120 – George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2020 calls for “lowering the criminal intent standard—from willful to knowing or reckless—to convict a law enforcement officer for misconduct in a federal prosecution.” The bill goes on to ask for “limits to qualified immunity as a defense to liability in a private civil action against a law enforcement officer or state correctional officer, and authorizes the Department of Justice to issue subpoenas in investigations of police departments for a pattern or practice of discrimination.”

This is just one example of government officials taking a stand against this type of behavior and sparking conversations about reform. But this doesn’t mean people should stop demanding for reform in the system. It’s important that the public continues to put pressure on law enforcement and higher officer holders so that the topic isn’t shoved under the rug. Without addressing the issue and making serious change, these senseless killings will only continue.

The argument about whether officers should be made to take accountability for the unnecessary and unproportional killing of minorities is ridiculous. The conversation should instead focus on the system that allows the number of these cases to continue to rise at an alarmingly fast rate.