Behind the scenes of a scandal

College admissions documentary reignites anger

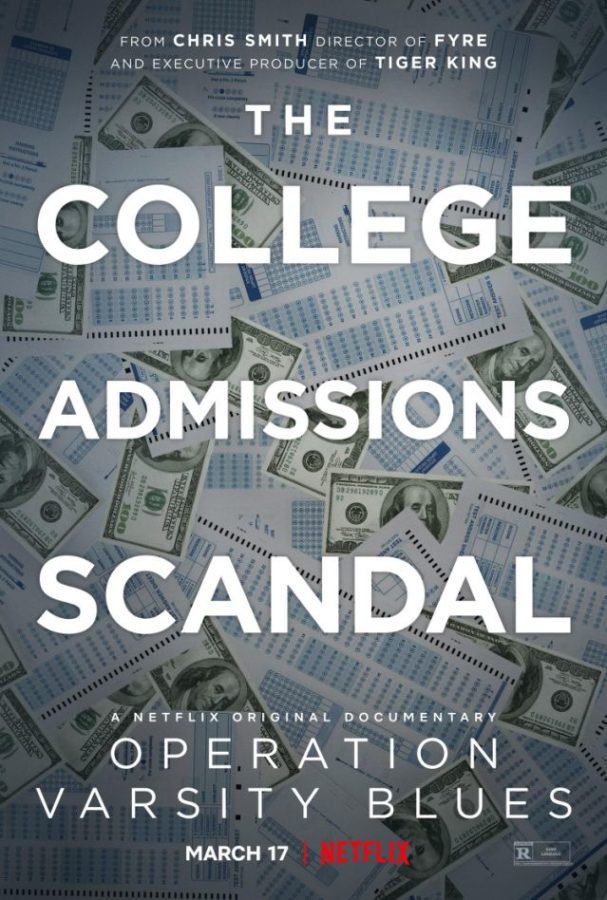

On March 17, Netflix released their original documentary “Operation Varsity Blues,” which explores the high-profile college admissions scandal that shook the nation. 5/5.

March 30, 2021

It was early in 2019 that the headlines started to break: “Federal racketeering sting reveals ‘side door’ into elite colleges,” “U.S. charges dozens of parents, coaches in massive college admissions scandal.” America broke into a frenzy. A couple of months later, the craze settled down and most of the country had all but forgotten about it.

Then, on March 17, 2021, Netflix released their new original documentary “Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal.” The documentary weaves together on-camera interviews, news footage and reenactments of phone calls to tell the story of Rick Singer (played by Matthew Modine), the mastermind behind the admissions scandal. It reignited anger over the scandal by shedding light on some of the lesser-known details.

It recounts how Singer started a college admissions counseling company, The Key, in 2007. While the company provided some legitimate college counseling, it also served as a front for bribery. Singer received tens of millions of dollars from wealthy actors, CEOs, lawyers and more to get their children into schools like Georgetown, Georgia Tech, UCLA and Berkeley.

Singer also received money through his Key Worldwide Foundation. The foundation masqueraded as a nonprofit that benefitted underprivileged children, and its 501(c)(3) status allowed the wealthy donors to get tax deductions for the money they gave Singer to get their children into college.

With the money, Singer paid off college officials (like athletic directors and admissions officers) to get his clients in through a “side door” where, rather than bribe colleges through direct donations, clients paid him to use dishonest tactics that would give their child a leg up in admissions. Singer photoshopped pictures of his clients participating in sports like water polo, for example, in order to help them secure spots as walk-ons at elite colleges. He also orchestrated cheating schemes that allowed students to receive higher scores on the ACT. In one phone call reenactment, Singer explains that he can get people in through his side door at Harvard for $1.2 million while claiming that one would have to donate $45 million directly to Harvard to get in through their “back door.”

The documentary interviews former federal prosecutor Robert Fisher, “Price of Admissions” author Daniel Golden, a handful of educational consultants, former clients of Singer and even former romantic partners. Rather than looking into the lead-up or legacy of the scandal, it focuses on the details of the process. It answers questions about where the money was coming from and going to, how Singer got students in by fabricating their involvement in sports and what tactics he was using to get higher ACT scores for clients.

In a less explicit way, “Operation Varsity Blues” also examines the question of who the villain is in the admissions scandal. The wealthy parents have been the go-to targets in the headlines, but the film turns the attention to another target: Singer. As the film goes on, the colleges themselves are added to the list of offenders as their front of innocence is chipped away. At one point, former Stanford admissions officer Jon Reider suggests that the scandal may actually be benefiting elite colleges because it adds to their repute of exclusivity.

Through its commentary and interviews, the film paints a picture of a network of individuals who played an already corrupt system that’s been strengthened by things like the U.S. News prestige scoring, elitism in colleges and social media pressure.

The interviews and commentary, however, were not the most unique features of the documentary; it was the reenacted conversations based on wiretapped phone calls that made the movie. The film used wiretap transcripts that the government released to make recreations of conversations that happened between Singer and his clients. While the idea of a fictional element in a documentary took some getting used to, by the end of the film, it was clear that it was the right move. It was a clever way to get around the fact that the filmmakers couldn’t easily tell the story through interviews (since most of the involved people are guilty and don’t want to be on camera). It also added a creative element that contributed to the story; in reenactment scenes, Singer’s casual “basketball coach” style clothing, which his former clients allege that he wore to add legitimacy to his position as a college admissions coach, juxtapose his lavish house and the tropical California scenery that makes up the backdrop of the scenes.

Going into it, I expected a documentary aimed at people who read the headlines but didn’t dive too deep into the details of the admissions scandal. In fact, it included information that even those who followed along with the events closely probably didn’t know, such as the reenactments of conversations Singer had with clients on the phone. For those who weren’t as up-to-date on the scandal, the film was a perfect summary. While it didn’t seek out a lot of new information or reveal anything groundbreaking, it turned a complicated series of events into a digestible and enjoyable story.

Another thing that makes the documentary worthwhile for those who are already informed about Varsity Blues is the new perspectives that it showcases. During the scandal’s time in the media spotlight, much of the buzz was focused on the big celebrity names or the colleges that were involved. “Operation Varsity Blues” focuses little attention on those subjects and instead looks at the characters who ran the scandal behind the scenes: Singer, the athletic directors and admissions officers, Mark Riddell (the proctor who helped students cheat on the ACT) and more.

Most notably for me, the documentary also included the perspective of students who weren’t involved in the scandal. In the opening scenes, there is a montage of students opening their college admission decisions. Initially, it seemed out of place and unnecessary, but eventually it was clear that the videos were there to communicate a message: these students are the real victims of this scandal. For every spot that a wealthy parent buys for their child, a deserving student loses their spot. Similar videos are sprinkled throughout the film and serve as a necessary attempt to include student voices directly. During college decision season, it was a relatable element that hits close to home for a lot of high school viewers. The videos also add to the film’s underlying commentary about elitism in admissions and the game that applying to colleges has become; it’s a game that wealthy students and their families can pay to win.

The documentary’s commentary on aptitude tests was one of the most interesting aspects and it furthered the conversation regarding how wealthier students can pay to win. It claims that these aptitude tests, like the ACT and SAT, are really a measure of family income. Many families can’t afford to pay $300 dollars an hour for a decent tutor or $1000 for a test prep course from Kaplan or Princeton Review, and even the wealthy families involved in the scandal who could afford that still chose to cheat simply because they had the money. They could afford the $75,000 price tag Singer charged to have scores falsified or to have someone else take the test.

The film gets into the grit of how deep the college admissions scandal goes — for decades, for example, wealthy parents have been paying to have their kids get learning disability accommodations to get more time on standardized testing. It’s these little things that wealthy kids have access to that make not just the corrupt corners in the shadows, but the entire system of admissions really messed up. Because of this, a documentary that, on the surface, seemed to be about a man who was corrupt and made immoral choices was really about something much deeper; it was about a man who was smart enough to make millions off an already corrupt system that allowed for that type of behavior to thrive, and this documentary opens the door for further conversation on that.

In the final moments, on-screen text reminds viewers that “the back door is still open for those willing to pay.” The text showing the couple weeks or months of sentencing these wealthy people got was not a satisfying conclusion and did not make you feel justice was served, but it was a reminder of how the college admissions corruption goes beyond just a few people — it truly is a system that will protect the wealthy from the consequences of their actions.