America’s government is aging

We need more youth representation in office

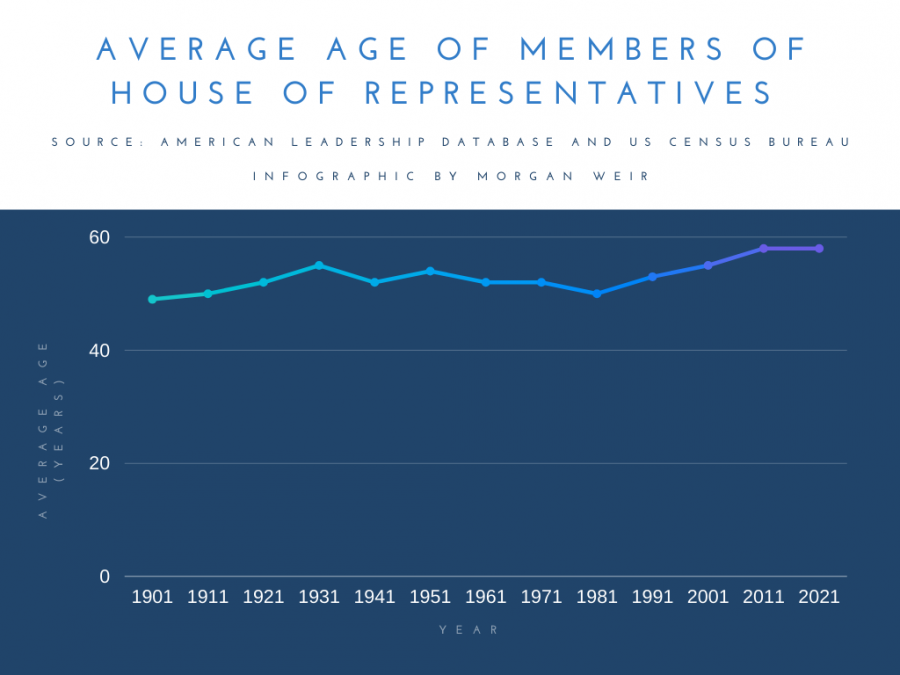

The average age of members of the House of Representatives has been increasing since the 1790s. In the past 120 years, it has made its way up to 58. While the median age in the US has also grown, it still remains under 40 – well under the current average age of US Representatives.

March 1, 2021

There are 535 members of Congress. Of those 535, only 39 were born in the 80s, and just one was born in the 90s. The average age of members of the current Congress is 59 years old, a full 23 years older than the country’s median age of 38. At age 34, Senator Jon Ossoff is the youngest sitting Senator and the first millennial in the Senate.

The average age of Congress members has been trending up for decades, with 2018’s 115th Congress being one of the oldest in history at an average age of 60. While other developed countries’ leaders have been steadily getting younger, at an average age of 54, the United States’ leaders have been getting older. When President Joe Biden was inaugurated in January at age 78, he became the country’s oldest president. Nancy Pelosi is the oldest person to hold the role of Speaker of the House at 80 years old. The Senate President Pro Tempore, Patrick Leahy, is also 80. Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer is 70, and Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell is 79.

With people over the age of 70 dominating American politics, youth voices and concerns are increasingly being shut out. Even though people under 40 make up the majority of the US population, they make up only a fraction of representatives in Congress. Right now, America’s aging government shows no signs of getting younger anytime soon, but if political parties and voters supported millennial politicians during campaign season, that could change. It’s time to reverse the trend of America’s aging government and make sure young people’s perspectives are represented in office.

In a 2018 Associated Press survey, two-thirds of Americans aged 15-34 said they wanted to see more people from their generation elected. Yet, clearly, young people are not being elected in high numbers; currently, only about 5% of state legislative seats are held by millennials.

It may be tempting to write off the lack of youth representation in Congress as the result of politically unengaged young people, but voter turnout from the 2020 election debunks that. Youth turnout surged to 53%, one of the highest it has ever been. There were also hundreds of millennials running for state and local offices across the country last year, though they often lost to more established politicians.

Even before 2020, the younger generations have been at the forefront of political change for most of American history. College students with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organized sit-ins and marches in the fight for civil rights during the 60s. High schoolers with March for Our Lives held school walkouts to demand gun reform in 2018. Youth leaders like Xiye Bastida, Greta Thunberg and Isra Hirsi with Extinction Rebellion, Sunrise Movement, Fridays for Future and other organizations are pushing for climate change action. Even within the walls of Millard West, clubs like EcoWest, Justice and Diversity League and Political Roundtable prove that young people are as interested in politics and as willing to get involved as adults are.

Despite all this, we have been denied seats at the table for decades. Youth are praised for their work, told by older generations that we are the future and the change the world needs. Yet, when election time comes around, all that time spent proving what we are capable of is ignored as older, established party leaders and incumbents don’t even let us in the door.

But, if political engagement isn’t the issue, why aren’t younger people being elected? The short answer is money. Running and winning a campaign takes a lot of funding – funding that newcomers aren’t likely to have compared to incumbents with established donor bases. During the 2020 election cycle, over $8.7 billion dollars were spent on federal Congressional races alone. This cost has risen dramatically in the past 10 years. In 2010, the money spent on federal Congressional races totaled $3.6 billion.

The political campaign system was built to keep older people in office. Politicians with large amounts of money behind them, like former President Trump, or those with a lot of political recognition, like President Biden, have much higher chances of winning and are usually older. It’s the reason why incumbents win their races for reelection over 90% of the time, and it’s part of the reason why new, young voices have so few opportunities to be heard in government.

Some young politicians like Pete Buttigieg, Josh Hawley, Madison Cawthorne and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have managed to make a name for themselves among older peers, but their stories of struggle against incumbents prove that the political system isn’t working for them. They need support, not just from voters, but from their political parties. Parties play a major role in deciding which candidates run for legislature, both nationally and locally. In 1975, 1981 and 1995, at a time when party control was not as strong, the average age of incoming senators was less than 50.

The Associated Press survey also found that people between the ages of 15-34 want to elect people who care about the things they care about, including healthcare, racial wealth gaps, student debt, climate change, abortion and immigration. While many of these issues impact people of all ages, it is undeniable that young people and old people have different political priorities and needs. Young people deserve public policy that responds to those needs. Recent studies have shown that with younger people in office, government policy and programs like welfare are oriented more to the concerns of young people.

Youth political representation matters because younger generations will be the ones left to deal with the consequences of the choices politicians are making right now. They will pay the price for the country’s massive national debt and Congress’ lack of responsible budgeting. They will bear the brunt of the climate catastrophe and the government’s lack of action to prevent it. If young people were given seats at the table, it would bring a sense of belonging for younger generations and help close the age divide in an American society that is more divided than ever.