Disney’s racist legacy

Diversity in animated films matters

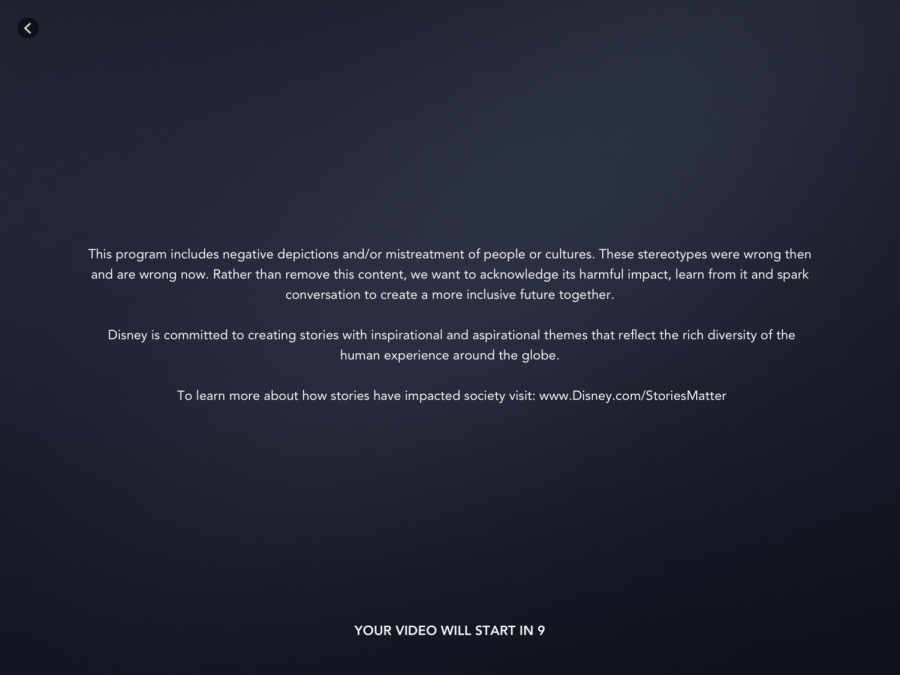

A disclaimer about racial stereotypes plays before Disney’s “Dumbo.” The disclaimer lasts for 12 seconds and can not be skipped. It also plays before movies like “The Aristocats” and “Peter Pan.”

January 14, 2021

If you watch an older animated movie on Disney+, you may see a disclaimer pop up at the beginning about racial stereotypes in the movie. The 12 second disclaimer acknowledges that the “negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures…were wrong then and are wrong now.” It plays before films like “Dumbo,” “Lady and the Tramp,” “Jungle Book,” “Peter Pan” and “The Aristocats.” The move is an attempt by Disney to address past controversies and turn them into an opportunity for conversation, according to the website that viewers are directed to in the disclaimer. But is it enough to undo Disney’s history of racism?

Disney has always marketed itself as wholesome and innocent. They have spent decades building a brand based around family, magic and fun. However, there isn’t anything cute or family friendly about racist stereotypes. It may be because of this contradiction that the company has been so reluctant to confront its own racist past.

The treatment of one of their most notorious (and outright racist) films, “Song of the South,” is one of many examples of Disney sweeping their problematic history under the rug rather than acknowledging it. When “Song of the South” was released in 1946, it wasn’t released on video due to the major backlash received for its racist overtones. Unlike many older Disney movies, it hasn’t been played in theaters since 1986, and Disney never released a DVD version of it. While most films from the studio’s beginning, like “Bambi” and “Snow White,” have been added to Disney+, “Song of the South” has been intentionally left off. Speaking on the decision to keep the movie off their streaming service, former Disney CEO Robert Iger said that allowing it to be seen “wouldn’t necessarily sit right or feel right to a number of people today,” and “it wouldn’t be in the best interest of our shareholders to bring it back, even though there would be some financial gain.” Clearly, the company doesn’t see, or isn’t willing to talk about, the controversies of their past and is more concerned with the financial consequences than the cultural ones despite their enormous influence.

“Song of the South” certainly wasn’t the first racially or culturally insensitive movie Disney made, nor was it the last. In “Dumbo,” for example, which was released in 1941, a group of crows, including one named Jim Crow, reenacted minstrel shows. In the movie’s “Song of the Roustabouts,” Black laborers sing the lyrics “we slave until we’re almost dead, we’re happy-hearted roustabouts.” In “Peter Pan,” released in 1953, Native Americans are referred to using the slur “redskins” and sing “What Makes the Red Man Red?” In “The Aristocats,” released in 1970, a cat with stereotypical East Asian features who is voiced by a white person plays the piano with chopsticks and sings in a poor, stereotyped accent.

Even in the 2009 film “Princess and the Frog,” which showcased Disney’s first Black princess, Tiana spent most of the movie as a frog, and while the movie did hit on some themes of sexism and gender limitations, it barely touched on the issue of racial limitations. Disney’s newest release, “Soul,” has faced similar criticism. While it was praised for showcasing a Black lead who is “recognizably Black while avoiding anything that recalled the racist stereotypes in old cartoons,” as The New York Times put it, it was criticized for once again turning the Black lead into a non-human entity for much of the film. Joe Gardener, the film’s main character and Pixar’s first ever Black lead, was represented not as a Black man, but as a blue figure.

“Soul” became only the fourth American animated feature ever with a Black leading character, as The New York Times noted. It is only the second produced by Walt Disney Animation Studios, which has made a total of 58 animated feature films. Clearly, representation is lacking.

Disney needs to finally do the work of accurately portraying the nuances of cultures, people and lifestyles that are often ignored. It will not erase the past decades of insensitive racial and cultural stereotyping, but it will be a step forward for representation in animated films. In a video on Disney’s website, Geena Davis, founder of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, says that “what children see sets the framework for what they believe is possible in life.” The stories we tell as a culture help everyone understand their place in the world. For adults, teens and children alike, representation matters.

Disney claims on their website that they are committed to “creating stories with inspirational and aspirational themes that reflect the rich diversity of the human experience around the globe,” but they don’t share any action plans for how they will achieve that. Disney needs to do more than show a disclaimer at the beginning of their movies. It’s not enough to acknowledge that they were wrong; they must take active steps to confront the cultural harm they’ve committed and do better going forward.

One thing the company can do is partner with smaller, diverse studios. Disney is doing just that with their upcoming animated series “Iwájú” by partnering with Kugali, a pan-African creative company based in West Africa. Whether this will be a regular feature of Disney’s animation process going forward or is nothing more than a marketing strategy is yet to be determined, but hopefully it will be more than just a one-time thing. As a cultural powerhouse and entertainment monopoly, the best thing Disney can do to help tell diverse stories is support diverse groups of people in telling them.

Another important step Disney should take is hiring a diverse staff of voice actors, animators, directors, producers and more to take part in the storytelling process. Walt Disney Animation is bringing on a more diverse group of directors for some of their upcoming projects, like “Raya and the Lost Dragon,” but, once again, it is unclear whether this commitment to diversity will be a long-term commitment.

Ultimately, one company being more inclusive is not going to end prejudice in global culture, and it isn’t going to undo the long history of racism in America. However, increased diversity and representation in animated films will at least be a start to telling stories that celebrate and showcase everyone rather than reinforcing a racist hierarchy.

Disney has a responsibility to its viewers, and to society at large, to do better. They have a duty to set aside the front of wholesomeness and purity that they try to market in favor of confronting the reality of their studio’s legacy. With new animated films that feature nonwhite identities and cultures, like “Encanto” and “Raya and the Lost Dragon” coming out in the next few years, it seems like the company is moving in the right direction. However, viewers will have to wait and see how people are portrayed in these movies and what other steps Disney will take long-term.