Stop policing people’s grammar

“Proper English” is a dangerous idea

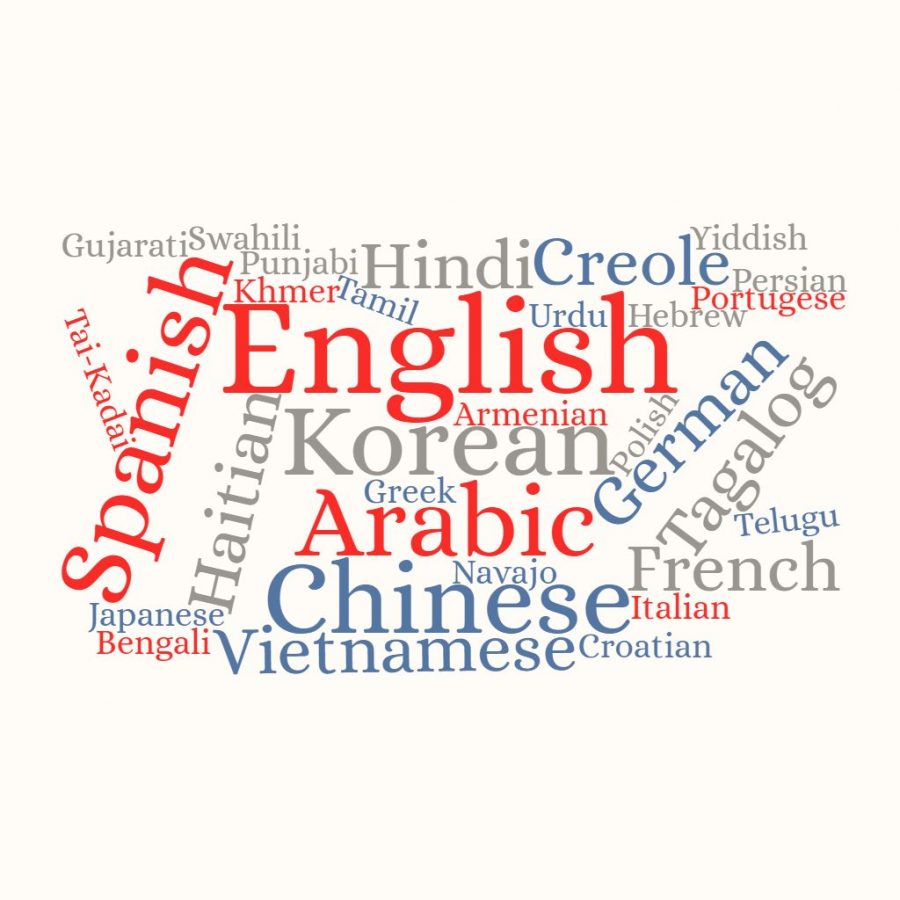

The US Census Bureau found that over 350 languages are spoken in the US. English, Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog and Vietnamese are some of the most common. Even within these languages, there are different dialects and varieties, making the US incredibly linguistically diverse.

September 4, 2020

Language is the centerpiece of culture. It’s about more than communication; it’s a shared tool that bonds us with people in our community. However, it can also become a barrier that isolates and differentiates us. It can quickly shift from a powerful tool to a weapon.

On a large scale, this often takes the form of forced assimilation and language erasure. African slaves in America were forced to learn English and abandon their native languages. Between 1860 and 1978, the US government funded boarding schools for indigenous Americans where students were physically punished for speaking their native languages in the name of promoting “civilization.” After the US overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, English was made the official language and anyone who was caught speaking or teaching the Hawaiian language was punished or socially ostracized. Government policing of language has a long and brutal history, rooted in white supremacy and colonialism.

People still weaponize language erasure today. In February, two women, who were speaking Spanish, were attacked in Boston. As they were kicking, punching and biting the mother and her 15 year old daughter, the attackers yelled, “This is America! Speak English!” The idea that immigrants, particularly Latinx people and people of color, should only speak English in America is, unfortunately, a common one, steeped in violent history. America is an incredibly diverse country and a huge variety of languages are spoken here. We should value and celebrate that, not erase and condemn it. It’s xenophobic and racist to police native languages and equate “English” with “American” when in reality America is incredibly linguistically diverse.

English is not the official language in America, but it is in over half of US states, and it is taught to be the supreme language. In Massachusetts, California and Arizona, there were laws in place up until 2016 and 2017 that got rid of bilingual programs and mandated English immersion programs for public school students who spoke another language. Many Americans and US states cling to the idea that English is the “language of the civilized.” Pushing this idea, whether through formal education programs or by policing people’s language, only reinforces the narrative that white American culture is supreme.

Despite the popularity of English immersion programs for non English speaking students, many American public schools don’t prioritize learning languages like Mandarin or Spanish, which are some of the most commonly spoken languages worldwide. The number of foreign language classes have been dropping in the last few years. Schools that go through all means necessary to teach English to young children but aren’t willing to put in any effort to educate students on other languages, especially given America’s history of language erasure, send a divisive message.

The racist undertones of language policing are further enforced by the idea of “proper English” and “broken English.” The phrase “proper English” is questionable considering that proper English usually means white, heteronormative English. This might not be such a bad thing if it weren’t for the fact that other dialects or variations of English, such as African American Vernacular English (AAVE), are considered improper and uneducated, and therefore anyone who speaks in those dialects is considered unintelligent. People who speak in English dialects that are deemed “improper” face discrimination in courts, schools and workplaces. They are stereotyped by an American society who misunderstands the complexity and culture behind language.

Language and grammar policing isn’t limited to institutions; individuals do it constantly. People often make assumptions about other people’s socioeconomic status, education or intelligence based on their grammar, accents, vocabulary or slang. Regardless of intention, it is wrong. Linguistic discrimination, or linguicism, is rooted in classist, ableist and xenophobic ideology and it often manifests in grammar policing. Usually, it doesn’t help anything. Despite the fact that seeming smart is often an underlying motivator, it only makes the person doing the language policing seem pedantic and judgmental, and it may make the person being judged feel uncomfortable.

When people police others’ language, they reveal their expectation of other people to bend or change their habits so that they can be more comfortable. Often, they are not willing to make the same effort for others, whether it be non-English speakers or people with accents, because they’ve been taught that English is supreme. This is exemplified in the act of changing language or dialect in different social situations, known as code-switching. Code-switching is prominent among Black people who speak AAVE, particularly those who are younger and college-educated. They feel like they need to change their way of speaking in order to fit into different social groups or workplaces, which can lead to problems with self-identity and burnout.

It’s not just a question of how we police peoples language and vocabulary but whose language we are policing in the first place. Slang is the perfect example of that. It doesn’t follow the grammatical rules of “proper English,” but most people don’t criticize teenagers for using slang. However, so much of the slang we give “young people” credit for actually comes from language spoken by Black, Latinx and queer people as far back as the early 1900’s. Phrases like spilling the tea, throwing shade and turn up originated in these communities as a way to defy the popular culture that shunned them, and marginalized people were mocked for speaking this way. Once mainstream US culture got hold of it, it suddenly became cool and quirky to speak that way.

In order to bridge cultural divides and promote diversity within America, we need to reevaluate what language reveals about national identity. We need to question how it promotes diversity, how our reaction to it can harbor violence, how our view of it breeds harmful stereotypes and how suppressing it narrows our worldview. Most importantly, once we’ve asked ourselves these questions, we need to stop policing people’s grammar.