The real problem with fake news

We need to consider the role we play in spreading misinformation

Fake news has become a prominent socio-political problem as politicians, news organizations and consumers grapple with whose responsibility it is to handle misinformation.

August 28, 2020

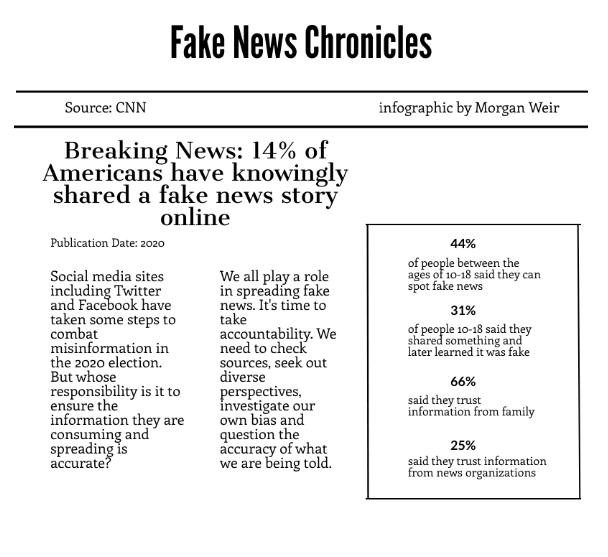

As the 2020 presidential election heats up, people are drawing a lot of comparisons with what happened four years ago. Fake news in particular has become a hot topic as November nears. Lies, hoaxes and misrepresented facts were pervasive across social media platforms during the 2016 election. The issue hasn’t gone away since then; in fact, it has become far more complex. Even after the 2016 election was over, President Trump turned “fake news” into a rallying cry. It has extended beyond campaign season and it’s extended beyond one political side. People point fingers at the other party, at politicians and at social media sites. They especially like to point fingers at the media. The one place that people do not place blame is in themselves.

People have long claimed that any information they don’t agree with is fake news. The Nazi Party did it in the 1930’s when they bashed the “Lügenpresse” or “lying press”. US politicians do it constantly, and so do their followers. What many people fail to recognize is that there are laws and regulations against libel, slander and publishing false claims that prevent news organizations from spreading complete misinformation.

However, these laws don’t necessarily apply everywhere that people receive news because the media is not limited to established news organizations. Especially in the modern day, “the media” is everywhere. It is Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Snapchat. It is the shows we watch and the books we read and the podcasts we listen to. If we want to have conversations about the media spreading misinformation, we need to change what we consider “the media.”

This is especially relevant for high schoolers. Around 54% of teenagers surveyed in a 2015 Common Sense Media survey said they get news weekly from social media sites including Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Half of the participants said they get it from YouTube. Only 41% said they get news from print or online news organizations.

While social media can be a powerful tool for quickly disseminating information, it also presents a new set of challenges. Unlike with traditional news articles or broadcasts, news on social media is often conveyed through bite-sized information in a short caption or a single photo. We end up reading headlines without reading the entire article or looking at captions without seeing the full picture, and we fill in the information gaps with our own assumptions.

Because of how quickly information travels and how quick people are to share posts, it’s difficult to contain or detect misinformation. Despite being considered fluent in social media, young people struggle with this to a surprising degree. A 2016 study from Stanford University involving almost 8,000 elementary to college-aged students found that students have trouble differentiating sponsored content from news stories, fake accounts from real ones and activist groups from neutral sources.

One possible reason for the shift to social media news is distrust in the “mainstream media,” which is a common sentiment in the conversation around fake news. Most people overlook the fact that the “mainstream media” is, for the most part, what we give leverage to. We choose what we consume and we choose what narrative we follow. It’s ignorant to shift all the blame on to the media without recognizing our own power and freedom to choose what we consume.

Because billionaires have a large stake in many of the United States’ major news publications, and a few large corporations own a large share of the media in general, we don’t always get to choose what stories get told. However, there are other options, and those options are largely ignored and unsupported. If the same people who complained about mainstream news sources being controlled by the corporations that fund them actually supported independent journalism, these sources might not have such a large influence over the stream of media.

Not only do we choose what we consume, but we choose how we consume it. Often in the conversation around fake news, people make “the media” out to be the villain. They paint a picture of a massive conspiracy by journalists to spread fear and lies. However popular this portrayal may be, journalists don’t spread fear; they spread information. We choose how we react.

It’s also not journalists’ job to help us find reputable sources and delicately piece together an easy-to-swallow story. It’s our own responsibility to learn how to consume information intelligently and intentionally. It’s our own responsibility to find reputable sources and to dig for the truth and to make sense of it. All sources and reporters have a certain degree of bias and it’s important to recognize it, but we have to remember that readers have bias, too. As consumers of news, it’s easy for us to be critical of what we are reading, but it’s not as easy for us to think about how we are reading it.

The problem is not fake news. The problem is that we have a society who uses news to justify and reinforce their own personal stereotypes and biases regardless of the truth. We don’t just need people who are critical of how trustworthy journalists and articles are; we need people who are critical of themselves. We need people who are willing to let new ideas change their worldview or their understanding of someone or their thoughts on their community.

This will not be the last election where misinformation plays a significant role. As social media becomes more ingrained in our society and way of life, it will inevitably have a big effect on politics. As high schoolers, who have grown up with social media news, become a larger part of the voting bloc, we will have to decide how we deal with the issue of fake news. Hopefully we will realize that the issue is larger than just the news that’s written–it’s how we consume it.