A cacophony of campaigns

Political ads need to be dialed back and tightened up

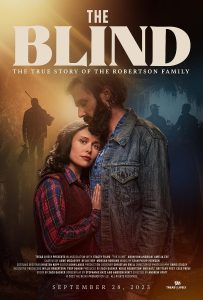

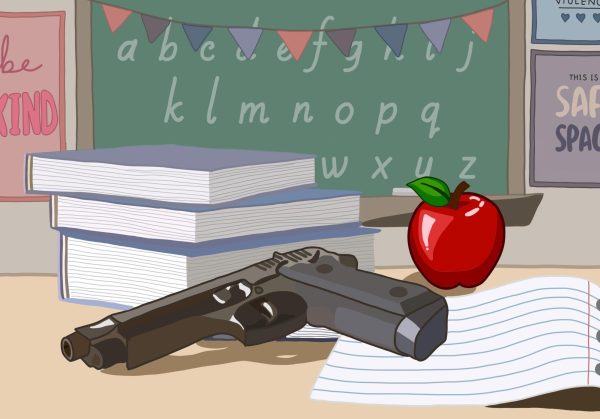

Photo by Matt Johnson (Creative Commons)

Don Bacon is running for re-election as US House Representative and faces opponent Kara Eastman. The two have created many ads, some promotional and others attacking. Either way, they’re getting more than enough air time.

October 28, 2020

With national and local elections right around the corner, political campaign advertisements have grown relentless in their interruption of daily life. It’s impossible to watch TV, grab your mail or even scroll through social media without the reminder to vote or not vote for certain people. Oftentimes, I walk away from political ads feeling more resistant to candidates and ideas I don’t care for—even candidates and concepts I’d normally hold in high regard.

A September study from the collaborative political science departments of Yale, UCLA and UCSD found that the swaying effects of political advertising are extremely “small regardless of context, message, sender or receiver.” In other words, while televised and digital ads are completely effective at being bothersome and irritating, they are ineffective at what politicians think they’re good for: persuasion.

This is especially true right now with less than one week to Election Day. I struggle to see how hopefuls like congressional representative nominees Don Bacon and Kara Eastman will impact decisions through media advertisements with so little time left. Not to mention, their efforts are fruitless towards around 20% of Nebraskan voters who have already sent in their ballots.

In attempting to change the frequency and timing of these political ads, we must also recognize how few restrictions there are in regard to fact-checking and ethicality. As Arizona Central writes, “While the Federal Election Commission requires TV and radio ads to provide information about who produced them, what is said in those ads has been deemed protected speech, even if it’s not true.” I find hypocrisy in the fact that commercial businesses are held to the truth in advertising laws of the Federal Trade Commission, but potential members of our very government do not have those same restrictions. Essentially, they have the legal opportunity to trick the American people—the people they are meant to serve and protect.

This leads me to wonder: Why? When being considerate and fair is so easy, why do candidates lose focus on their own campaigns to drag down someone else? After all, the previously mentioned study showed that “attack advertisements are about as effective in achieving their goals as promotional advertisements and that PAC [Political Action Committee] or SuperPAC sponsored advertisements are no more effective than those sponsored by candidates.” With both attack and promotional ads equally efficacious, it only makes sense for candidates to boost their own perceptions in positive ways.

Beyond morality, it’s clear that the legislation is just as non-existent in the realm of political advertising on social media. The Federal Election Commission and Federal Communications Commission provide close to zero regulations and instead leave it up to media companies, like Facebook, to decide what’s allowed and what’s not. In 2016, the Trump campaign spent millions fine-tuning their targeted ad operations on Facebook and left many questioning the rectitude of the approach. Although there have been few limitations on ads put in place since then, Facebook will ban new political ads on Facebook and Instagram for the week following October 27th. In the end, no matter what a social platform says about its lack of targeting, things like IP addresses and public voter files can still impact the ads consumers come across.

We need to focus on allocating time, effort, resources and money into effective and less negative forms of campaigning. We need to listen to the political science experts that have done the research and proved that televised and digital advertising does close to nothing. Imagine the problems we could solve if politicians shifted from creating hateful, repetitive ads to spending their money and time in needy communities. Political ads are maddening, not only in format but also in the way they waste opportunities to promote change.